Avoiding Food Allergies: Keep in Mind The Big 9

Feeding a child with food allergies can be quite challenging. A major concern for parents is trying to feed their infants who may already have eczema or other allergic manifestations, including urticaria, anaphylaxis or wheezing.

The presence of food allergies remains increasing worldwide, with a peak prevalence of 6%-8% in children at 1 year old.1 That’s approximately 5.6 million children in the United States alone.2

In Asia, prevalence rates are not as high but are increasing in some countries including Japan (5%-10%) and Korea (5.3%).3

Food allergy, arising from an immune response to food exposure, should not be confused with “food intolerance”, which is not immune-mediated.4

For example, a child may be allergic to cow’s milk due to an immunologic response to certain milk proteins; alternatively, the child may be intolerant to milk due to the inability to digest lactose.

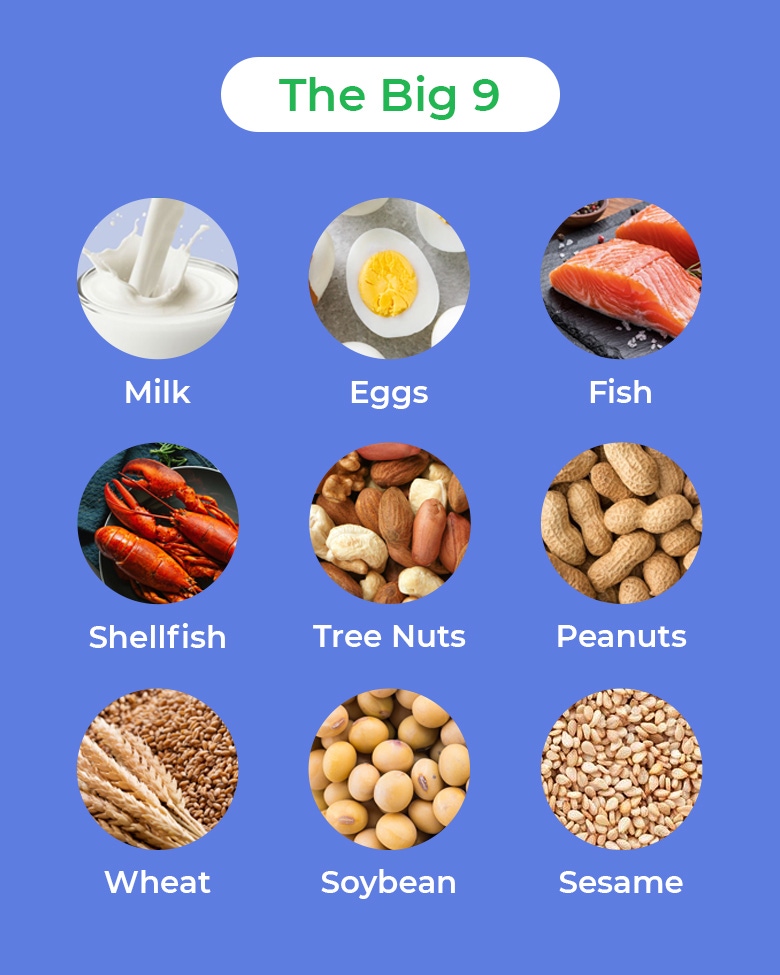

Any food can cause an allergic reaction but we have what we call “The Big 9” which are the top food items causing 90% of reactions. These include cow’s milk, eggs, fish, shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, soybean and sesame.5

DIAGNOSING FOOD ALLERGIES

Figure 1. The nine major food allergens 5-6

MANAGING ALLERGIES THROUGH DIET

Patients are put on elimination diets when a specific food allergen becomes difficult to pinpoint.7, 8 This can be both diagnostic and therapeutic with an individualized approach based on a child’s history.

Elimination diets should not be confused with “hypoallergenic diets” that are often advised to patients. According to an article by Dr. Ballmer-Weber, “a hypoallergenic diet in a proper sense, does not exist. The prescription of a dietary treatment for allergic diseases is highly dependent on an exact allergologic diagnosis.”9

A hypoallergenic diet consisting of a list of foods to avoid is a misnomer. This is often advised without considering the child’s complete history, only to have them return to a regular diet after symptoms have resolved. However, mistakes in avoidance are common and may affect the child’s nutrient intake.

Avoidance is the most important aspect of management after confirming the diagnosis.10 Maternal dietary avoidance of the allergen is considered for breast-fed infants. Introduction of allergenic foods at 4-6 months old is recommended in high-risk infants who are developmentally ready and can tolerate allergenic foods.11 A diverse diet for older children with allergies can help avoid nutrient deficiencies.12

Depending on the severity, reminding parents to always have emergency medications and the contact details of their allergists is vital. Emergency medications may range from antihistamines, topical medications or epinephrine auto-injectors. As most food allergies that appear during infancy or childhood are outgrown, regular follow-ups are important to monitor for resolution and to ensure proper food reintroduction and adequate nutritional support.

References:

- Keet C, Wood, R. Food allergy in children: Prevalence, natural history and monitoring for resolution. UpToDate. 2021. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/food-allergy-in-children-prevalence-natural-history-and-monitoring-for-resolution.

- Gupta RS, Warren CM, Smith BM, et al. The Public Health Impact of Parent-Reported Childhood Food Allergies in the United States. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6):e20181235.

- Tham EH, Shek LP, Van Bever HP, et al. Early introduction of allergenic foods for the prevention of food allergy from an Asian perspective-An Asia Pacific Association of Pediatric Allergy, Respirology & Immunology (APAPARI) consensus statement. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2018 Feb;29(1):18-27. Available at: 10.1111/pai.12820. Epub 2017 Nov 22. PMID: 29068090.

- Boyce JA, Assa'ad A, Burks AW, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: summary of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010 Dec; 126(6 Suppl):S1-58.

- Food and Drug Association. Food allergen labeling and consumer protection Act of 2004 (FALCPA) [Internet]. [Cited 22 January 2022]. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-allergensgluten-free-guidance-documents-regulatory-information/food-allergen-labeling-and-consumer-protection-act-2004-falcpa.

- Food and Drug Administration. Food Allergies [Internet]. [Cited 19 May 2022]. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/food-allergies.

- Ebisawa M, Ballmer-Weber BK, et al. Food allergy: Molecular basis and clinical practice. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2015; 101:209-220.

- Wood RA. Diagnostic elimination diets and oral food provocation. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2015; 101:87-95.

- Ballmer-Weber BK. The hypo-allergic diet. Ther Umsch. 2000 Mar;57(3):121-7. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1024/0040-5930.57.3.121.

- Venter C, Groetch M, et al. A patient-specific approach to develop an exclusion diet to manage food allergy in infants and children. Clin Exp Allergy. 2018 Feb; 48(2):121-137.

- Fleischer DM, Spergel JM, Assa'ad AH, Pongracic JA. Primary prevention of allergic disease through nutritional interventions. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013 Jan;1(1):29-36.

- Sicherer S. Management of food allergy: Avoidance. UpToDate. 2021. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/management-of-food-allergy-avoidance.

If you liked this post you may also like