Protein: The facts

1. What are proteins?

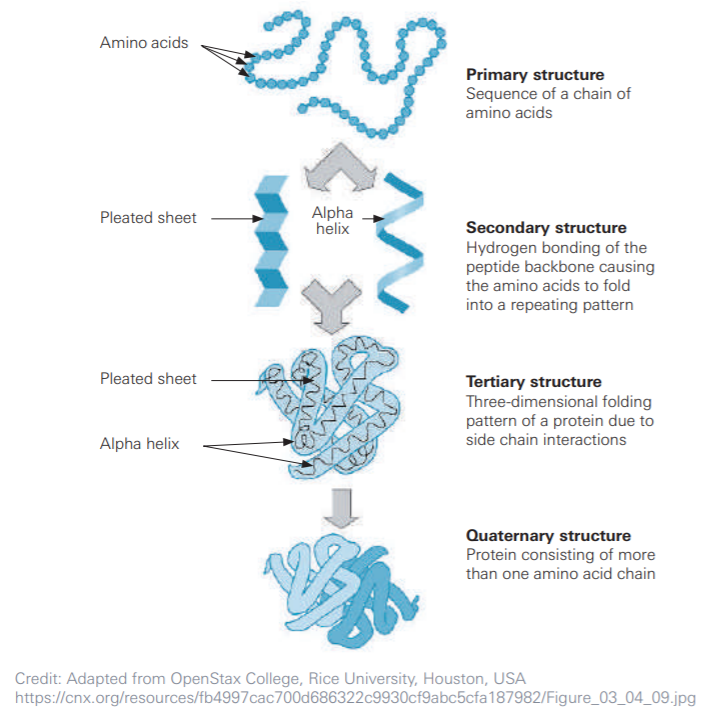

• Proteins are large, complex molecules made up of hundreds of smaller units called amino acids that are attached to one another by peptide bonds, forming a long polymer chain.

• There are 20 different amino acids, and each protein contains a unique combination of these.

• These chains twist, bend and fold in different ways to create specific threedimensional structures, such as corkscrew-like coils called alpha-helices or flat sections called beta-sheets.

• Some proteins are made up of multiple amino acid strands that assemble together into a fully functional structure.

• The way in which these structures form often dictate their specific physiological function.

2. Why are proteins needed in our diet?

• Proteins are major functional and structural components of all body cells, and participate in virtually all biological processes.

• Proteins provide amino acids that are used to build and maintain bones, muscles and skin, and produce key molecules such as enzymes, hormones, neurotransmitters, and antibodies.

• Amino acids are classified into three groups: − Essential amino acids which cannot be produced by the body, and must be supplied by the diet (histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine). − Non-essential amino acids which are made by the body from the normal breakdown of proteins. − Conditionally essential amino acids which, under certain physiological conditions, are synthesized only in limited amounts (e.g. arginine, cysteine, glutamine, glycine, proline, tyrosine).

• The roles of proteins expand beyond their role in maintaining body protein mass and satisfying metabolic demands for biosynthetic pathways. Other important body functions include immunity and host defenses, linear growth and associated mental development.

• Moreover, amino acids are not only building blocks of proteins but are also important by themselves, for multiple regulatory functions in cells. For example, leucine is specifically involved in muscle protein synthesis, glutamate in gut energy supply, tryptophan in serotonin synthesis and arginine in nitric oxide production. Amino acids also act as signal transducers involved in several cell signaling mechanisms in the body.

3. How are proteins digested and absorbed?

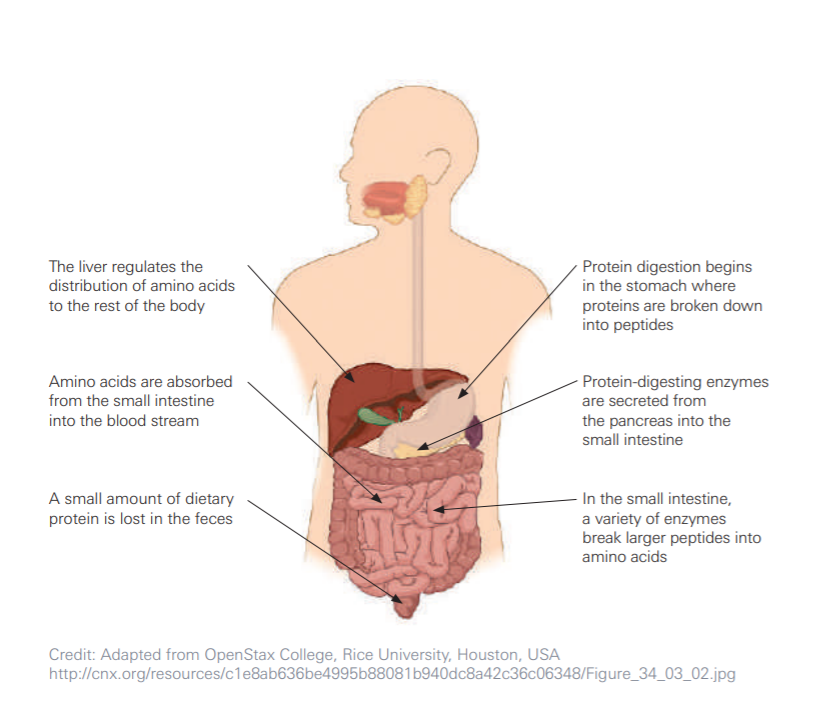

• The digestion of dietary proteins starts in the stomach with contractions in the presence of hydrochloric acid and proteases resulting in the proteins being broken down into smaller molecules known as peptides.

• These peptides progress down the digestive tract where they are exposed to protein digesting enzymes and further broken down into amino acids, a process that takes place in the ileum enabling their absorption into the blood stream.

• The absorbed amino acids may be used by individual cells for the re-assembly of new proteins involved in specific cellular functions.

• Proteins in lean tissue are constantly broken down and re-synthesized. During this process, amino acids may be recycled and reused or excreted.

• Under some conditions such as overnight fasting, amino acids may be used to produce energy by getting converted to sugar molecules (which can be then taken-up by the brain for example).

4. What are the dietary requirements of proteins?

• Due to the rapid turnover rate of body protein stores, there is a need for regular intake of amino acids in sufficient amounts to maintain good health.

• The amount required depends on several factors such as age and health status. If protein or essential amino acid intake is limited, the body may break down its own proteincontaining tissue to fill the gap.

• Traditionally, dietary protein recommendations have been based on preventing deficiency, taking into account the metabolic demand for the maintenance of the body, as well as protein requirements for growth during infancy and adolescence, or during pregnancy and lactation.

• The basic daily recommendation for protein intake ranges from 0.80 to 0.83 g per kilogram of body weight in generally healthy adults [1-3]. This translates into 48-50 g for a woman (60 kg) and 64-66 g for a man (80 kg) per day.

• Protein requirements are highest during the first years of life due to the rapid increase in growth, and then remain constant during adulthood, including older age [2, 3]. Scientific research is currently looking at whether or not elderly individuals would require greater dietary protein intake.

5. How much protein is consumed globally?

• In European countries, average protein intakes vary between 12 to 20 % of total energy intake for both men and women [3]. Similarly, in North America, average protein intakes were estimated at 15-16% of total energy intake [4].

• The worldwide average dietary protein consumption is 77 g/day [5]. Significant differences exist between the amounts consumed in developed countries (mean: 103 g/day), the developing world (mean: 70 g/day) and subSaharan regions (mean: 55 g/day, two times less than developed countries).

• However, protein inadequacy in terms of quantity and quality, remains a major nutritional problem in poor regions of the world [6]. For example, Africa and South Asia have an estimated 10% to 30% of children suffering from protein malnutrition [7].

6. What are the main sources of protein?

• Animal-based protein sources include meat, fish, dairy products, eggs and insects. A standard serving size of lean meat or poultry contains about 25 g of protein. One glass of cow’s milk, soy milk, or yogurt contain about 8 g of protein [8].

• Plant-based protein sources include nuts, seeds, tubers, legumes, lentils, grains, algae and fungi/yeasts. Cereals, grains, nuts, and vegetables contain about 2 g of protein per serving [8].

• The dietary quality of proteins is usually evaluated by the Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) which takes into account protein digestibility and amino acid composition [9]. The highest quality proteins will be the ones with the highest digestibility, and containing the essential amino acids in sufficient amounts to meet dietary requirements. More recently, further adaptations of the method have been proposed [10], but are not yet fully implemented.

• It is commonly agreed that proteins from animal origin are of high nutritional quality and therefore play a significant role in most diets. However, the nutritional quality of proteins from plant sources can be equally as high. For example, soybean and potato meet the required level in essential amino acids.

• Other plant protein sources may also provide all the essential amino acids, but the amounts may be lower depending on the plant source. For example, grains and some starchy roots (e.g. cassava. yam, but not potato) are limited in lysine. Some legumes (e.g. pea, lupin, but not soybean) are limited in sulfur amino acids (methionine and cysteine).

• Overall, eating a variety of unrefined grains, legumes, seeds, nuts, and vegetables throughout the day generally contributes to adequate intake of quality proteins.

7. What are the health effects of dietary proteins?

• Recent research has begun to focus on the relationship between dietary proteins and specific health outcomes such as cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, sarcopenia and obesity.

• Protein has been shown to impact satiety and therefore appetite control which may lead to reduced food intake overall [11]. However a strong cause and effect relationship is lacking.

• While some studies have found that the protein source (animal vs. plant) affects health outcomes, a variety of low-fat and lean protein sources are generally recommended for overall good health. The NRC recently initiated and published a systematic review concluding that the intake of plantsourced proteins and, in particular, soy protein containing isoflavones, as compared to animal-sourced proteins were associated with lower risk factors related to cardiovascular disease, i.e., hypercholesterolemia and hypertension [12].

• The timing of protein intake has been linked to several health outcomes in adulthood. Low protein intake at breakfast has been associated to age-related frailty. Furthermore, an even distribution of protein intake across the day has been shown to induce greater accrual of lean tissue as compared to an uneven protein intake across the day [13].

• Proteins may also be responsible for food allergies [14]. Most common food groups known to cause allergy include egg, peanut, tree nut, wheat, soy, sesame, fish and shellfish [15].

8. Is it better to have more protein?

• There is no apparent benefit of consuming dietary protein at levels exceeding the current recommendations for the general healthy adult population [16].

• Although a safe upper limit for protein intake has not yet been established, an intake of twice the recommended protein is generally considered safe for adults [3].

• During infancy, higher protein intakes have been associated with more rapid weight gain and higher body mass index compared to lower protein intakes [17, 18], and these outcomes have been linked to increased risk of obesity later in life [19, 20].

• Eating excessive amounts of protein may also come at the expense of other much needed nutrients.

9. How can protein fit into a healthy diet?

• Proteins are an essential part of the daily diet. As macronutrients, they provide energy (4 kcal/g) and are the main source of nitrogen for the human body for the maintenance of appropriate levels of amino acids, peptides and proteins.

• Regular consumption of a diet with a balanced proportion of nutrients provides enough proteins without the need of additional protein supplementation.

• Foods from both animal and plant sources may contain similar levels of protein. However, some high-protein foods are healthier than others because of what comes along with the protein, i.e. more or less amounts of healthy fats, fiber or hidden salt.

10.Are plant-sourced proteins more sustainable than animal-sourced proteins?

• When compared to plant-based agriculture, livestock production has a higher environmental impact relative to freshwater use, extensive land requirements, and greenhouse gas produced [21]. Accordingly, vegetarian diets tend to have lower greenhouse gas emissions in comparison to nonvegetarian diets [22].

• Promoting a shift in food patterns to a more plant-based diet and an increase in fat-free and low-fat protein sources is an increasingly recommended strategy to reduce the human impact on the environment [23].

• However, indiscriminate recommendations to increase plant-based foods can lead to the improvement in some nutrients but may also have possible unintended dietary consequences, i.e. risk of inadequate supply of some fatty acids, proteins, vitamins, minerals [24]. • It is therefore important to equally consider nutrition and environmental impact of any dietary shifts [25].