From Cradle to Playground: Optimising Early Childhood Nutrition for Lifelong Health

Optimising nutrition in early life remains a central challenge for parents, caregivers, and professionals caring for infants and young children. Historically, the main focus was on preventing deficiency diseases such as rickets, caused by a lack of vitamin D, and scurvy, resulting from inadequate vitamin C. However, the modern challenge extends far beyond preventing such deficiencies. Nutrition during infancy and early childhood is now recognised as a foundation for lifelong health, influencing growth, cognitive development, and the risk of chronic disease.

Globally, 22% of children under five experience stunting (low height-for-age) and 7% experience wasting (low weight-for-height), with the greatest burden occurring in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (Martens, 2023). At the same time, excessive intake of energy and macronutrients during infancy can lead to rapid growth, defined as an upward crossing of one major centile space (approximately 0.67 SD) on growth charts (Ong and Loos, 2006). This pattern, observed most commonly among formula-fed infants, may reflect the higher protein content of formula compared with human milk (Singhal and Lucas, 2004). Rapid early growth is associated with a higher risk of childhood obesity, and WHO estimates that around 37 million children under five are now overweight or obese.

This coexistence of under- and over-nutrition—often within the same community or even household—is known as the double burden of malnutrition. The challenge, therefore, is to optimise feeding during infancy and early childhood to minimise the risks of both extremes and their associated diseases.

Breastfeeding remains the optimal feeding method for most infants up to around six months of age (WHO, 2023). However, it is increasingly recognised that breastmilk alone may not fully meet micronutrient requirements beyond this age (Moore et al., 2025). From about six months, complementary foods should be introduced to meet rising energy and micronutrient needs (WHO, 2023). The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has long provided guidance on adequate micronutrient intakes during infancy. Yet, recent findings from the Mothers, Infants and Lactation Quality (MILQ) study suggest these reference values may require revision. Median nutrient concentrations in breastmilk from exclusively breastfed infants aged 1–6 months were found to be considerably lower than the IOM’s recommended adequate intakes (Moore et al., 2025). These findings highlight the need to re-evaluate assumptions about adequacy and consider updates to supplementation guidance.

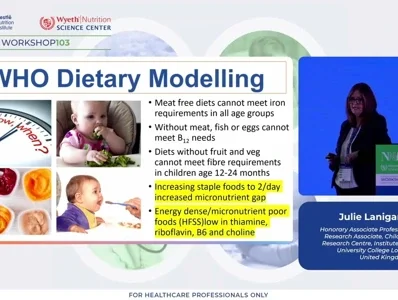

In its most recent guidance on complementary feeding, WHO developed theoretical ‘optimal’ menus through dietary modelling to minimise the risk of micronutrient deficiencies. However, these models did not account for the influence of excess macronutrient intake. This omission is concerning, as surveys and meta-analyses consistently report that complementary diets are high in protein, often increasing up to three-fold during this period. Evidence from systematic reviews demonstrates a strong association between high protein intake in infancy and greater risk of obesity in later childhood.

The complementary feeding period represents a critical transition, as children shift toward the family diet. Dietary patterns become established early—often by the age of three—and tend to persist into later life. Given the strong association between healthy dietary patterns and improved physical and cognitive outcomes, supporting the development of healthy eating behaviours in early childhood is vital. Encouraging balanced, nutrient-dense, and appropriately portioned diets can help prevent both deficiency and excess, setting the foundation for healthy growth and long-term wellbeing.

References

Mertens, A., Benjamin-Chung, J., Colford, J.M. et al. Causes and consequences of child growth faltering in low-resource settings. Nature 621, 568–576 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06501-x

Ong, K.K. and Loos, R.J.F. (2006), Rapid infancy weight gain and subsequent obesity: Systematic reviews and hopeful suggestions. Acta Pædiatrica, 95: 904-908. https://doi.org/10.1080/08035250600719754

Singhal, A and Lucas, A. Early origins of cardiovascular disease: is there a unifying hypothesis? The Lancet, Volume 363, Issue 9421, 1642 – 1645

WHO Guideline for complementary feeding of infants and young children 6-23 months of age. 16th October 2023. Accessed October 2025: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240081864

Moore, S.E. et al. Future Applications of Human Milk Reference Values for Nutrients: A Global Resource for Maternal and Child Nutrition Research, Advances in Nutrition, 2025, In Press.