Milk Lipids: A Complex Nutrient Delivery System

Abstract

The evolution of lactation and the composition, structures, and functions of milk’s bio- polymers illustrates that the Darwinian pressure on lactation selected for gene products with considerable structural complexity and diverse functions within the digestive system. For example, complex sugar polymers – oligosaccharides – possess unique proper- ties in guiding the growth of intestinal bacteria that are not possible by feeding their simple sugars. The proteins of milk are diverse with some exhibiting enzymatic activities towards other milk components rendering those components both more digestible but also releasing biologically active products. Thus, research into milk’s biopolymers has been most enlightening when milk was investigated for the formation and disassembly of its structures and for the functions within the infant. To date however, the most complex structure in mammalian milk, the fat globule, has not been effectively examined beyond its simple composition. The globules of milk are heterogeneous in size, composition, and function. With new research tools, scientists are beginning to understand the mechanisms that control the assembly of globules in the mammary gland and the disassembly within the infant.

Introduction

Milk fat has been largely ignored by diet and health research apart from linking fat to levels of cholesterol in blood. As a result, milk fat has been viewed as a net damaging contribution to human diets and even for infants. Such a negative value is not justified by more broadly based biological perspectives. Computational analysis of the evolution of the repertoire of mammalian genes responsible for lactation produced an unexpected conclusion. The most conserved sequence identities within the lactation subset of genes through mammalian evolution are the genes responsible for lipid secretion [1]. From a purely evolutionary conservation perspective, such results position milk as a lipid delivery system. Nonetheless, it is not clear from disease protection or long-term performance what lipids are providing to infants. Similarly, it is not evident when genetic, environmental or nutritional factors in maternal mammary gland compromise the synthesis of milk lipids. This lack of mechanistic understanding of milk synthesis and globule assembly is an important barrier to policy for dietary intakes for mothers. Without a mechanistic understanding of functions of milk lipids, it is not possible to develop methods that are capable of diagnosing functional impairments in infants due to insufficiencies or excesses in particular fatty acids, complex lipids, or even metabolic cofactors. The diversity of lipid molecules in milk implies a diversity of functions, yet scientists are still focusing almost exclusively on fatty acids. Lipids are far more complex, and in that complexity resides the assembly of cellular membranes, components of dispersed particles, epithelial barriers in skin, surfactant lipids in lungs and vesicles within and without cellular compartments. In addition to diverse structural roles, lipids provide an array of substrates for metabolic fuel, and they provide a precursor pool for a range of signaling molecules. Recent developments in biochemistry, gene annotation, and biophysics are enabling a renewed focus on the synthesis of milk lipids within the mammary gland. As structures are identified, they are being assigned novel functions within the infant. Saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids are becoming recognized as metabolic signal molecules acting systemically. The complex composition of human milk lipids directs a spontaneous self-assembly process during digestion creating structures at the nanometer length scale that enhance absorption of a wide range of nutrients.

Assembling Lipid Particles in the Mammary Epithelia

The assembly of complex lipids into highly organized bilayer membrane structures is the central organizational and energetic paradigm of biology. However, lipids provide a variety of other structural assemblies to higher organisms in particular as transport. The milk fat globule is one of biology’s more prodigious lipid transport systems. The particles themselves are highly disperse with sizes spanning three orders of magnitude and vary with stage of lactation, health of the mother, etc., with the average diameter varying between 1 and 10 μm [2]. The fat globule is a core of triacylglycerides assembled within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of the mammary epithelial cell from fatty acids of dietary, adipose depot, and lipogenic origins. This core of triacylglyceride is coated by a single monolayer of phospholipids derived from the ER membrane [3]. The milk fat globule is unique in containing also an intact bilayer membrane, which enrobes the globule as it exits the epithelial cell. This membrane as a result is com- posed of the lipids and proteins of the epithelial cell plasma membrane, including significant quantities of cholesterol, phosphatidylcholine, and sphingomyelin [4, 5]. Research has documented that these complex lipids have effects on composition and function of tissues literally from intestine to brain [6–8]. Yet one of the most important determinants of both composition and structure, globule size, is poorly understood. New research methods and models are mak- ing it possible to interrogate the more dynamic and complex lipid structures that are integral to the structures and functions of milk lipids.

The basic steps of globule assembly in the mammary epithelia are described [9]. Triglyceride synthesis by enzymes within the ER gives rise to an inert lipid phase of triglycerides bounded by a monolayer of ER phospholipids that is released into the cytoplasm as a spherical lipid particle. What happens after their formation is both the most unique property of milk fat globules and their least understood. Globules migrating towards the apical membrane fuse into larger discrete particles, and then the membrane and particle surfaces become enriched in key proteins notably xanthine oxidase and butyrophilin. At this stage, the particles’ outer surface interacts with the inner face of the plasma membrane, and the entire particle with surrounding plasma membrane is excreted as an intact milkfat globule.

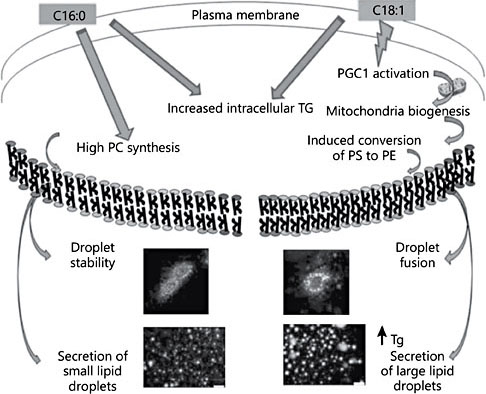

The most important determinants of globule size are the flux of triglycerides into the nascent particle within the ER, their release into the cytosol and the subsequent fusion (or not) of these particles prior to attachment with the plasma membrane and secretion. Triglyceride flux is driven by the substrate fatty acid availability and the net energy charge within the cell. Breakthrough new research demonstrates that these same determinants are responsible for particle fusion [10]. Central to these breakthroughs is the realization that specific fatty acids are more than simple substrates to triglyceride formation, they influence the metabolic pathways and biophysical events that guide particle formation, composition, and fusion (Fig. 1). Lipid synthesis is metabolically controlled in part by the PGC1 family of transcription coactivators that drive the expression of the concert of genes necessary to assemble mitochondria and synthesize lipid particles [11]. PGC1 is upregulated in the mammary epithelia by palmitic and oleic acids yet asymmetrically. Palmitic acid enhanced triglyceride and phosphatidyl choline concentration. Oleic acid enhanced triglyceride production and PGC1 activation and mitochondrial biosynthesis with a net increase in phosphatidyl ethanolamine concentration. This difference in phospholipid composition has an important effect on particle fusion events. As a membrane constituent, phosphatidyl ethanolamine is fusagenic. Thus, with these insightful breakthroughs in the basic mechanisms of particle fusion and the metabolic production of fusagenic phospholipids, guiding globule size distribution is becoming an accessible mammary gland outcome.

Fig. 1. Assembly of lipid globules within the mammary gland. Fatty acids with distinct metabolic activities and their consequences to biophysical events are indicated. C16:0, palmitic acid; C18:1, oleic acid; PGC1, PPARγ coactivator 1; PS, phosphatidylserine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PC, phosphatidylcholine; Tg, triglyceride. Modified from Co- hen et al. [23].

Milk Fat Globule Disassembly

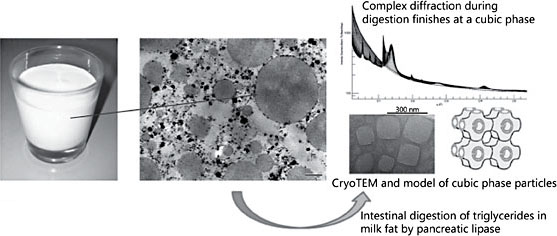

To date, little research has addressed the implications of the structural dimensions of human milk fat globules within the intestine of the infant. The retention of milk’s lipid production through the evolution of lactation in mammals implies that this remarkable structure is of considerable functional value to the mother-infant pair [1]. However, the techniques necessary to describe the structures of lipids in dynamic detail have not been available [4]. New physics technologies that are capable of interrogating the complex structures of lipids as the nanometer length scale and the time dimension of digestion are emerging [12]. While the spontaneous assembly of phospholipids into bimolecular mem- branes is the signature feature of lipid evolution, complex lipids spontaneously form a wide variety of three-dimensional structures from membranes to micelles to cubic phases [13]. These observations of purified lipids have been difficult to translate into biological mechanisms however. Why is the physical science not been taken to the biological dimension? The very nature of the forces underlying the spontaneous, rapid assembly of lipids into ephemeral, diaphanous structures is the reason the traditional experimental strategies of biochemistry are so disabled. The tools that worked so well on the “rugged” molecules of biology – proteins, polysaccharides, and polynucleotides – are insufficient in characterizing the soft structures of lipids. This is changing with the emergence of techniques designed to capture structural information on the length and time scales relevant to biological structures. One of the more actionable targets of lipid structures is the development of drug delivery systems tailored to the poor solubility of many therapeutically attractive but poorly bioavailable drug candidates [14]. The ultra- high intensity of coherent X-rays emerging from synchrotron sources enables techniques such as synchrotron small angle X-ray scattering to obtain diffraction patterns over much shorter time frames. This speed of diffraction measurement is capable of capturing transient lipid phases during digestion [15]. The pharmaceutical question is whether complex lipid phases can enhance drug delivery. It is also possible to ask the basic mechanistic question: do different lipid mixtures form distinct phases as they undergo the hydrolytic reactions of lipid digestion? By going biological instead of chemical, Ben Boyd’s group answered both questions at once [16, 17]. While the majority of lipid mixtures exhibit the appearance of micellar and lamellar phases during real time digestions, only milk lipids have produced a transient but highly robust signal associated with an extensive cubic phase. The implications of the formation of cubic phases during digestion are profound to the processes of nutrient absorption. Cubic phases are bicontinuous three-dimensional structures. The nature of the cubic phase means that there is effectively both a water phase and a lipid phase existing simultaneously as the continuous phase providing an unrestricted path for free diffusion across extend- ed-length scales for both water-soluble and lipid-soluble nutrients within the gut. The remarkable properties of these complex phases are their thermodynamic spontaneity. The formation of cubic phases with definable three-dimensional structure at the nanometer-length scale, extending for millimeters, does not require apparatus, energy, or template. These phases are the consequence of the composition of the lipids themselves, and they form spontaneously (Fig. 2). Strikingly, the complex lipids of milk form cubic phases during digestion, whereas the lipid mixtures found in formula do not [16].

Fig. 2. Milk lipid structures: macroscopic, microscopic, and diffraction patterns during digestion.

Lipids as Metabolic Signals

The dossier of lipid molecules documented to exhibit a signaling function and trigger and/or regulate cellular processes continues to grow. Many of these follow classic pathways in which protein receptors bind to different lipids transducing cellular events downstream into cellular processes [18, 19]. The oxylipins are lipid signals of local stress. The essential n-6-polyunsaturated fatty acids and in particular arachidonic acid have been demonstrated to provide these signaling functions [20].

Lipids signal to a wide range of biological processes. Their interaction with fuel metabolism and transport may be of particular importance to the development of metabolic regulation within infants. Although the majority of scientific research has focused on the essential fatty acids that must be obtained within the maternal diet, actions of the fatty acids made within the mammary gland are emerging as important as signaling molecules. Palmitic acid is the end product of fatty acid synthesis and is ubiquitous throughout biology. Palmitic acid is: a constituent fatty acid in cellular membranes; a fuel, producing 106 moles of ATP energy via beta oxidation; is acylated to various membrane proteins; and is a major component of storage lipids.

Now to this list must be added signaling. Puigserver and Spiegelman [21] discovered the functions controlled by a protein complex that they termed the PPAR gene transcription coactivator (PGC-1α). This transcription factor co-activator assembles protein regulatory units in the nucleus to control mitochondrial biogenesis. This laboratory made an equally important realization that when exposed to high levels of palmitic acid, liver cells both in vivo and in vitro actively turned on a closely related protein, PGC-1β [19]. PGC-1β simultaneously controlled fatty acid synthesis, triglyceride assembly, phospholipid synthesis and cholesterol biosynthesis. Their work identified the molecular switch linking dietary saturated fat and serum cholesterol as PGC-1β, and its most potent ligand is palmitic acid. Thus, palmitic acid is the signal activating PGC-1β and its cellular functions. By this transcription mechanism, the liver regulates the net production of very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) and their molecular constituents. Palmitic acid acts as a hepatic signal to stimulate VLDL synthesis and assembly. This specific signaling action in the liver and to VLDL production may be important both in infancy and throughout life.

Palmitoleic acid (16:1n7) is formed by the desaturation of palmitic acid by the stearoyl CoA desaturase enzyme. In practice, palmitoleic acid is produced when the enzymes of fatty acid synthesis and stearoyl CoA desaturase are more active than the elongase enzyme converting palmitic to stearic acid. This is typically true during active lipogenesis in humans and other animals. Cao et al. [22] identified and made a bold prediction characterizing palmitoleic acid as a novel lipokine, or lipid hormone involved in regulating the insulin-sensitizing effects of diet. Their studies are a demonstration of palmitoleate as a lipid signal, and a unifying model of metabolic products acting to control whole body fuel metabolism.

These are examples of signaling systems based on non-essential fatty acids regulating cellular, tissue, and whole body functions. Each of these lipid signals is conspicuously present in human milk. In view of these potentially immediate benefits of dietary lipids in infant health, it seems prudent to consider the complexity of lipids within human breast milk as an important asset that pursuing more simplified compositions puts at risk.

Conclusions

Lipids in milk are highly diverse, and their retention throughout evolution is a compelling story of biological structure and function. Though the research is not complete, principles can be taken forward in considering optimal dietary lipid compositions and structures for infancy. The biosynthesis of fatty acids and complex lipids within the mammary gland is a relatively variable series of processes depending on genetics, diet, maternal physiology, and metabolic status. This variability poses both a challenge and an opportunity. Understanding how globules are synthesized and assembled has proven to be a daunting task. Nonetheless, as the basic mechanistic principles are emerging, opportunities are also emerging to guide these processes towards more healthy, protective, and functional lipid systems. Similarly, the diversity of composition is revealing a diversity of functions within the mammary gland and the infant. The roles of lipid molecules in signaling are proving to be astonishingly diverse. Whereas lipid signaling was once thought to be a simple response to stress via the oxygenation of polyunsaturated fatty acids, a host of lipid molecules are now implicated in normal metabolism, physiology, immunology, and even cognition and behavior. Finally, lipids are a unique class of biomolecules because of the structures that they make within and outside cells. The evolution of mammalian milk has retained the unique fat globule structure across marsupials and all mammals. Finally, new biophysical tools are beginning to assign specific properties to the structural dimension of dietary lipids. Once again, biology is teaching chemistry and pharmacology how best to guide complex processes to desired outcomes.

References

- 1 Lemay DG, Lynn DJ, Martin WF, et al: The bovine lactation genome: insights into the evolution of mammalian milk. Genome Biol 2009;10:R43.

- 2 Hamosh M, Peterson JA, Henderson TR, et al: Protective function of human milk: the milk fat globule. Semin Perinatol 1999;23: 242–249.

- 3 Bauman DE, Griinari JM: Nutritional regulation of milk fat synthesis. Annu Rev Nutr 2003;23:203–227.

- 4 Argov-Argaman N, Smilowitz JT, Bricarello DA, et al: Lactosomes: structural and compositional classification of unique nanometer- sized protein lipid particles of human milk. J Agric Food Chem 2010;58:11234–11242.

- 5 German JB, Dillard CJ: Composition, structure and absorption of milk lipids: a source of energy, fat-soluble nutrients and bioactive molecules. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2006;46: 57–92.

- 6 Schnabl KL, Larsen B, Van Aerde JE, et al: Gangliosides protect bowel in an infant mod- el of necrotizing enterocolitis by suppressing proinflammatory signals. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009;49:382–392.

- 7 McJarrow P, Schnell N, Jumpsen J, Clandinin T: Influence of dietary gangliosides on neo-natal brain development. Nutr Rev 2009;67: 451–463.

- 8 Carlson SE: Early determinants of development: a lipid perspective. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89:1523S–1529S.

- 9 Heid HW, Keenan TW: Intracellular origin and secretion of milk fat globules. Eur J Cell Biol 2005;84:245–258.

- 10 Cohen BC, Raz C, Shamay A, Argov-Arga- man N: Lipid droplet fusion in mammary epithelial cells is regulated by phosphatidyl- ethanolamine metabolism. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 2017;22:235–249.

- 11 Wu Z, Puigserver P, Andersson U, et al: Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial bio- genesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell 1999;98:115– 124.

- 12 Warren DB, Anby MU, Hawley A, Boyd BJ: Real time evolution of liquid crystalline nanostructure during the digestion of formulation lipids using synchrotron small-angle X-ray scattering. Langmuir 2011;27:9528– 9534.

- 13 Hyde S: Identification of lyotropic liquid crystalline mesophases; in Holmberg K (ed): Handbook of Applied Surface and Colloid Chemistry. Chichester, John Wiley & Sons, 2001, pp 299–332.

- 14 Porter CJH, Trevaskis NL, Charman WN: Lipids and lipid-based formulations: optimizing the oral delivery of lipophilic drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2007;6:231–248.

- 15 Salentinig S, Phan S, Khan J, et al: Formation of highly organized nanostructures during the digestion of milk. ACS Nano 2013;7: 10904–10911.

- 16 Salentinig S, Phan S, Hawley A, Boyd BJ: Self- assembly structure formation during the digestion of human breast milk. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2015;54:1600–1603.

- 17 Clulow AJ, Salim M, Hawley A, Boyd BJ: A closer look at the behaviour of milk lipids during digestion. Chem Phys Lipids 2018; 211:107–116.

- 18 Zeidan YH, Hannun YA: The acid sphingo- myelinase/ceramide pathway: biomedical significance and mechanisms of regulation. Curr Mol Med 2010;10:454–466.

- 19 Lin J, Yang R, Tarr PT, et al: Hyperlipidemic effects of dietary saturated fats mediated through PGC-1beta coactivation of SREBP. Cell 2005;120:261–273.

- 20 Gupta S, Maurya MR, Stephens DL, et al: An integrated model of eicosanoid metabolism and signaling based on lipidomics flux analysis. Biophys J 2009;96:4542–4551.

- 21 Puigserver P, Spiegelman BM: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1 alpha): transcriptional coactivator and metabolic regulator. Endocr Rev 2003;24:78–90.

- 22 Cao H, Gerhold K, Mayers JR, et al: Identification of a lipokine, a lipid hormone linking adipose tissue to systemic metabolism. Cell 2008;134:933–944.

- 23 Cohen BC, Shamay A, Argov-Argaman N: Regulation of lipid droplet size in mammary epithelial cells by remodeling of membrane lipid composition – a potential mechanism. PLoS One 2015;10:e0121645.