Gut Microbiota and Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics

Gut Microbiota and Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics

Hania Szajewska

Key Messages

- A balanced gut microbiota is crucial for health. Conversely, an altered gut microbiota composition and/or activity (dysbiosis) contributes to diseases

- Targeting gut microbiota using probiotics and/or prebiotics has the potential to treat or even prevent diseases

- Not all probiotics and/or prebiotics are equal. The clinical effects and safety of any of them used alone or in combination should be evaluated separately

- The use of probiotics or prebiotics with no documented health benefits should be discouraged

Gut Microbiota Is Not a Forgotten Organ Any More

Gut microbiota refers to organisms (bacteria, viruses, or eukaryotes) that are present in the gut. It has a profound impact on immunological, nutritional, physiological, and protective processes [1], it has been linked to health, and it is considered by some to represent a new organ in the human body. While it is often called “the forgotten organ” [2], the gut microbiota is no longer forgotten. On the contrary, it is a hot topic for research, as documented by the rapidly increasing number of scientific papers on this subject as well as coverage in the lay press, TV and radio programs, and social media.

Dysbiosis

Dysbiosis refers to altered gut microbiota composition and/or activity. A low diversity of gut microbiota may be considered a marker of dysbiosis. At least in part, dysbiosis contributes to the development and progression of diseases such as allergy, obesity, irritable bowel syndrome, necrotizing enterocolitis, type 1 diabetes, and autism (in addition to other factors such as genes or environmental factors) [3]. However, the exact underlying mechanisms remain unclear. It remains to be determined whether the gut microbiota alterations are a cause or a consequence of these disorders. For none of the diseases has a specific “microbiota signature” been identified. The lack of standardized methods for microbiota evaluation may be responsible for inconsistencies among studies. Still, the association between low diversity of gut microbiota, which may be considered a marker of dysbiosis, and disease has been documented in a number of studies. From a functional point of view, low gut microbiota diversity is associated with reduced butyrate-producing bacteria, increased mucus degradation potential, reduced hydrogen and methane production potential combined with increased hydrogen sulfide formation potential, and an increased potential to manage oxidative stress [4].

Modulating the Gut Microbiota

Targeting the gut microbiome with pro-biotics, prebiotics, or synbiotics could potentially benefit human health and reduce the risk of diseases. Other methods, not discussed here, include antibiotics and fecal microbiota transplants.

Probiotics

Probiotics are “live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host” [5]. The most commonly used probiotics are Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species, and a species of yeast (Saccharomyces boulardii). Possible main mechanisms of probiotic action include:

- production of metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids, the majority of which are acetate, propionate, and butyrate;

- modulation of the composition and/or activity of the host microbiota (e.g., through colonization);

- enhancement of epithelial barrier integrity;

- modulation of the host immune system;

- adherence to the mucosa and epithelium with inhibition of pathogen adhesion and/or growth;

- production of enzymes (e.g., lactase to promote lactose digestion);

- production of bacteriocins.

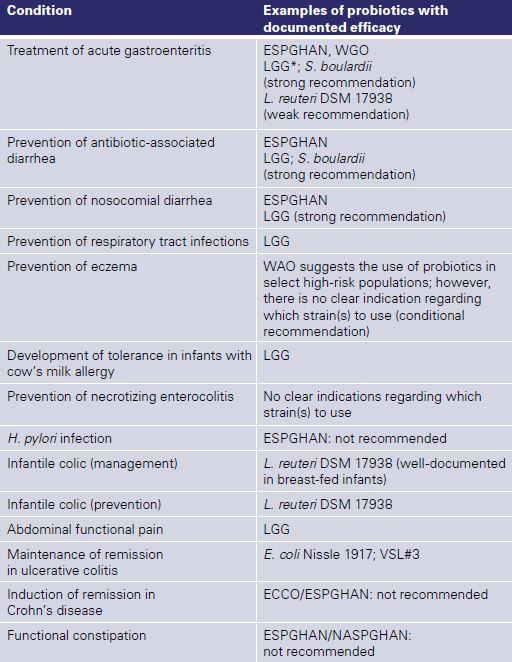

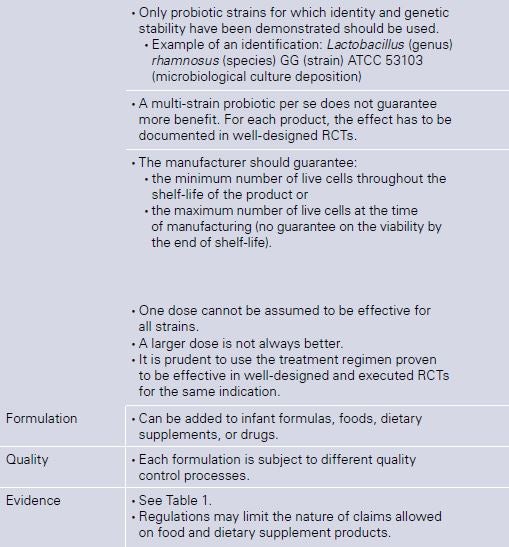

For a summary of the clinical effects of probiotics in children [6], see Table 1. Considering that probiotics have many strain-specific effects, the focus should be on individual probiotic strains not on probiotics in general. The clinical effects and safety of any single probiotic or combination of pro-biotics should not be extrapolated to other probiotics. For a guide on how to choose a probiotic, see Table 2.

Table 1. Effects of probiotics in children (based on ref. [6])

ECCO, European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization; ESPGHAN, European Society for

Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition; LGG, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG;NASPGHAN, North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology andNutrition; WAO, World Allergy Organization; WGO, World Gastroenterology Organization * New data question the effcacy of LGG [16]

Prebiotics

A prebiotic is “a substrate that is selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit” [7]. One example of naturally occurring prebiotics are human milk oligosaccharides. Selected human milk oligosaccharides, such as 2-fucosylactose and lacto-N-neo-tetraose, are currently being added to some infant formulas [8, 9]. Inulin, oligofructose, fructooligosaccharides, galactofructose, and galactooligosaccharides are other examples of commonly used and studied prebiotics, as they increase the fecal counts of bifidobacteria or certain butyrate producers.

In the pediatric population, selected prebiotics have the potential to:

- soften stool, which may be beneficial in some infants and has been consistently documented with the administration of prebiotic-supplemented infant formulas (primarily with a mixture of short-chain galactooligosaccharides and long-chain fructooligosaccharides) [10];

- reduce rates of gastrointestinal or respiratory infections (documented in some trials only) [11];

- reduce allergy (the World Allergy Organization recommends the use of prebiotics in non-exclusively breastfed infants; however, no specific recommendations with regard to the choice of prebiotics were given) [12].

Table 2. How to choose a probiotic [based on ref. 15]

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; RCTs, randomized controlled trials.

Synbiotics

Probiotics and prebiotics combined to act synergistically are called “synbiotics.” Potentially, synbiotics have stronger effects on gut microbiota than either probiotics or prebiotics alone. Compared to probiotics or prebiotics, data on the efficacy of synbiotics are scarce.

In the pediatric population, synbiotics have the potential to:

- reduce the risk of sepsis (L. plantarum ATCC 202195 plus frucotooligosaccharides reduced the risk of neonatal sepsis in a developing country) [13];

- contribute to the management of atopic dermatitis in children aged =1 year with mixed strains of probiotic bacteria (but they cannot be used as prevention) [14].

What Is Next?

Gaining a better understanding of how microbiota is linked to health and disease is needed to develop next-generation modulators of the gut microbiota. The latter, once developed, need to be evaluated in well-designed and executed randomized controlled trials with clinically important outcome measures. In pediatrics, these outcomes relate to the risk of allergy, gastrointestinal and respiratory tract infections, overweight/obesity, and neurodevelopment. For now, it is best to recommend the use of only those probiotics and/or prebiotics with documented efficacy and safety and to use a regimen (dose and formulation, duration of treatment) proven to be effective in well-designed trials for the same indication.

References

- Lynch SV, Pedersen O. The human intestinal microbiome in health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 15;375(24):2369–79.

- Marchesi JR, Adams DH, Fava F, et al. The gut microbiota and host health: a new clinical frontier. Gut. 2016;65:330–9.

- Gilbert JA, Blaser MJ, Caporaso JG, Jansson JK, Lynch SV, Knight R. Current understanding of the human microbiome. Nat Med. 2018 Apr 10;24(4):392–400.

- WGO Handbook on Gut Microbes. http://www.worldgastroenterology.org.

- Hill C, Guarner F, Reid G, Gibson GR, Merenstein DJ, Pot B, et al. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014 Aug;11(8):506–14.

- Szajewska H. What are the indications for using probiotics in children? Arch Dis Child. 2016 Apr;101(4):398–403.

- Gibson GR, Hutkins R, Sanders ME, Prescott SL, Reimer RA, Salminen SJ, et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Aug;14(8):491–502.

- Puccio G, Alliet P, Cajozzo C, Janssens E, Corsello G, Sprenger N, et al. Effects of infant formula with human milk oligosaccharides on growth and morbidity: a randomized multicenter trial. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017 Apr;64(4):624–31.

- Marriage BJ, Buck RH, Goehring KC, Oliver JS, Williams JA. Infants fed a lower calorie formula with 2 FL show growth and 2 FL uptake like breast-fed infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015 Dec;61(6):649–58.

- Skórka A, Pies´cik-Lech M, Kolodziej M, Szajewska H. Infant formulae supplemented with prebiotics: are they better than unsupplemented formulae? An updated systematic review. Br J Nutr. 2018 Apr;119(7):810–25.

- Lohner S, Küllenberg D, Antes G, Decsi T, Meerpohl JJ. Prebiotics in healthy infants and children for prevention of acute infectious diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. 2014 Aug;72(8):523–31.

- Cuello-Garcia CA, Fiocchi A, Pawankar R, Yepes-Nuñez JJ, Morgano GP, Zhang Y, et al. World Allergy Organization-McMaster University Guidelines for Allergic Disease Prevention (GLAD-P): Prebiotics. World Allergy Organ J. 2016 Mar 1;9:10.

- Panigrahi P, Parida S, Nanda NC, Satpathy R, Pradhan L, Chandel DS, et al. A randomized synbiotic trial to prevent sepsis among infants in rural India. Nature. 2017 Aug 24;548(7668):407–12. Erratum in: Nature. 2017 Nov 29.

- Chang YS, Trivedi MK, Jha A, Lin YF, Dimaano L, García-Romero MT. Synbiotics for prevention and treatment of atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Mar;170(3):236–42.

- https://isappscience.org

- Schnadower D, Tarr PI, Casper TC, Gorelick MH, Dean JM, O'Connell KJ, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG versus placebo for acute gastroenteritis in children. N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 22;379(21):2002–2014.