Feeding Patterns of Infants and Toddlers: The Mexico Case Study

Abstract

Understanding the feeding patterns of Mexican infants and toddlers has required large efforts due to the lack of recent reliable data. The double burden of obesity and micro- nutrient undernutrition is a public health problem in Mexico. This chapter reviews a series of papers reporting the FITS (Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study) Mexico effort. Secondary data analyses from a nationally representative sample of over 5,000 children from the Mexican National Nutrition and Health Study 2012 ENSANUT (Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición) were used to review the feeding and drinking patterns of Mexican infants and young children. Feeding patterns in Mexican children are established early in life. Low rates of exclusive breastfeeding were found in infants under 6 months of age. Only half of 6- to 47.9-month-old children consumed fruits, and 80% did not consume any vegetables (including potatoes) on the day of the survey. From the age of 12 months, more than 80% consumed sweets or sweetened beverages on any given day. For nutrients, 61% of infants 6–11.9 months old did not meet the estimated average requirement for iron, indicating a nutritional risk. High intakes of food groups with poor micronutrient and high energy levels might explain the nutritional condition for the Mexican population. Mexican experts have used this information to make recommendations and establish complementary feeding guidelines for healthy infants. Public policy and practice must now change accordingly.

Introduction

Understanding the feeding patterns of Mexican infants and toddlers has required large efforts due to the lack of recent reliable data. Mexico is well known as one of the world’s largest countries in terms of overweight and obesity. In 2017, more than 70% of the Mexican adult population 15–74 years of age is either obese or overweight [1]. Childhood overweight and obesity is also very prevalent in Mexico. Overweight and obesity affects 9.7% of preschool children from birth to 4 years of age. It rapidly increases to 34.4% of children from 5 to 11 years. Adolescents also have an overall prevalence of 34.9% for over- weight and obesity [2]. Alongside with obesity, anemia is a big health concern in Mexico. According to the 2016 Mexican National Nutrition and Health Study ENSANUT (Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición), 26.9% of children 1–4 years of age are anemic, and the rate was 38.3% among those 12–24 months of age [3].

The double burden of obesity and micronutrient undernutrition has raised the alarm, identifying the need to discover how and when inadequate consumption of nutrients is taking place in such a diverse country. The types of foods and beverages that children consume have drastically changed in recent years, though there is poor factual knowledge around this matter. Patterns of food and beverage consumption established in such early stages of development may remain unchanged into adulthood. Already, Mexican children and adolescents have an adult-like pattern of food consumption, putting them on a trajectory for overweight, obesity, and inadequate nutrient intakes.

Another issue in Mexico is that many physicians and health care professionals remain as bystanders in the practice of complementary feeding, offering little advice to parents. There is a consensus recommendation for the introduction of complementary feeding that serves as a national reference [4]. Breastfeeding is strongly recommended. The national policy is for exclusive breastfeeding for at least 6 months, and introduction of complementary foods should not start before this age.

Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study in Mexico

The FITS (Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study) Mexico was planned to address the lack of knowledge of the actual feeding patterns of Mexican children. Secondary data analyses from a nationally representative sample of over 5,000 children from ENSANUT 2012 were used to provide an in-depth understanding of the feeding and drinking patterns of Mexican children [5–8]. ENSANUT 2012 is a cross-sectional, population-based survey to characterize the health and nutritional status of the Mexican population [9]. The survey used a multistage, stratified, and clustered sampling system drawn to represent all states, 4 geographic regions, and socioeconomic strata in Mexico. The data were collected from 50,528 Mexican households with a response rate of 87%. The survey protocol and data collection instruments were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Mexican National Institute of Public Health. Written informed consent was obtained from each eligible person 18 years and older and from the parent or caregiver of participants under 18 years. A total of 2,057 children from birth up to 4 years of age were used in the current analyses, including infants 0–5.9 months (n = 182), infants 6–11.9 months (n = 229), toddlers 12–23.9 months (n = 538), and young children 24–47.9 months old (n = 1,108).

One dietary 24-h recall was collected for each child through a face-to-face interview by trained interviewers with the parent or caregiver; a second dietary recall for a randomly selected subsample of children (10%) was collected on a different day. Details were provided on all foods and beverages and the amounts consumed during the previous 24 h. Amounts were estimated using common household measurement aids (including spoons, cups, slices, and handfuls, etc.) and converted to grams and milliliters depending on the type of food consumed. An automated 5-step multiple-pass method was used, and data were collected on both weekdays and weekend days [10].

Breast milk amounts were estimated based on the child’s age and the total amount of other milks (infant formula and cow’s milk) reported on the recall day [11, 12]. Energy intakes, macronutrients, and food sources of nutrients were analyzed. Appropriate and inappropriate foods and beverages, as defined by Mexican and international organizations, were considered as the end point for analyses of feeding patterns.

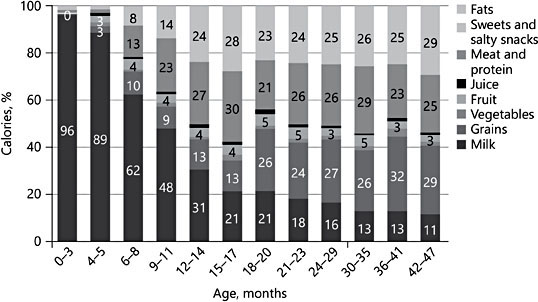

Feeding patterns in Mexican children are established early in life (Fig. 1). Diets shift quickly from an all-milk diet to a diet high in grains, protein foods (including dried beans), and sweets, but low in fruits and vegetables. By the age of 12 months, young children in Mexico are eating a diverse diet with approximately 25% of their energy coming from sweets, sweetened beverages, and salty snacks. Foods and beverages with poor micronutrient content and high energy might explain the nutritional condition for the Mexican population through all age groups.

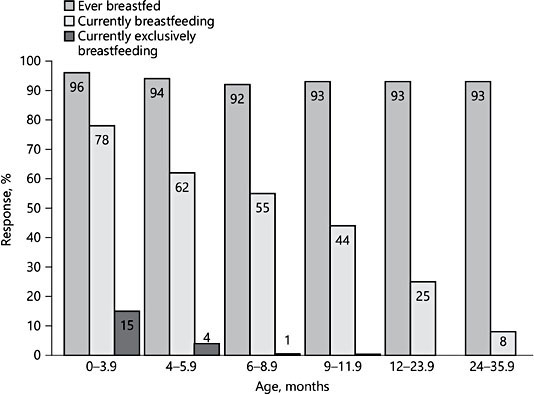

Low rates of exclusive breastfeeding were found in infants under the age of 6 months [5]. Breastfeeding initiation was high (96%), but exclusive breastfeeding was low: only 15% among 0- to 3.9-month-old infants and 4% among 4- to 5.9-month-old infants according to the 24-h recall (Fig. 2). Partial breastfeeding was much more common, with 62–78% of young infants receiving breast milk. During the survey, moms were directly asked about months of breastfeeding, and 66% answered that they had breastfed for at least 6 months. This is in clear contrast to exclusive breastfeeding rates for 6 months reported from the 24-h recall in the same survey. Both answers are correct, mainly due to the early use of inadequate substitutes of human milk during the first 6 months of age. Almost 10% of 4- to 5-month-old babies consumed whole cow’s milk, and up to 29% of 6- to 11-month-old infants did as well. All types of milk consumption decreased drastically from 93% at 6 months of age down to 54% at 24 months. This pattern seems to stay that way all through childhood. Breastfeeding in Mexican infants is inversely related to the socioeconomic status. Only 64% of higher-income moms of 0- to 5.9-month-old infants breastfeed compared to 81% of those in the lower-tertile socioeconomic status.

Fig. 1. Percent of energy intake from food groups consumed by Mexican children aged 0–47 months

Fig. 2. Breastfeeding rates among Mexican infants and young children

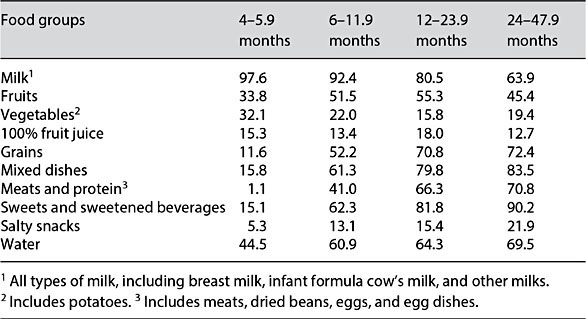

Table 1. Percent of Mexican infants and young children consuming foods and beverages from different food groups

Complementary foods were commonly introduced between 4 and 5.9 months of age, and only a small percentage of infants younger than 4 months consumed any foods or beverages other than breast milk or infant formula [5]. From 4 to 5.9 months of age, the most commonly consumed foods were fruits (33.8%) and vegetables including potatoes (32.1%) (Table 1). Other complementary foods introduced at this age included grains (12%), mixed dishes (16%), and sweets (15%), including sweetened beverages. Few infants received iron-rich food sources, such as fortified infant cereals or meat. More than one half of 12- to 47.9-month-old children (55.3%) consumed fruits, but approximately 80% did not consume any vegetable as a distinct serving on the day of the recall. After 24 months of age, over 90% of children consumed some type of sweets or sugar- sweetened beverages on any given day [5].

Infant cereals are unpopular among the Mexican population. They are frequently perceived by moms to promote rapid weight gain in small infants. Cereals are given through infant formulas as beverages or as baby food in rare cases of low weight gain. Only 9% of 6- to 8-month- infants consume iron-fortified cereals according to the ENSANUT 2012 survey. Other carbohydrates are frequently used in baby diets. Pasta soups, sweetened breads (pan de dulce), cookies, and crackers as well as adult cereals are frequently consumed but are not iron fortified or not fortified at levels to meet infant needs. Other iron-rich foods such as meats and poultry have a quite low consumption. Meat consumption in 6- to 12-month-old infants goes from 7 to 20% around the country. After their first birthday, only about 25% of toddlers eat meat on any given day. This low consumption of iron-fortified food may explain that 61% of 6- to 11-month-old infants do not reach the daily estimated adequate requirement of iron. The median consumption of iron at that age is only 3.4 mg per day [3]. As mentioned previously, iron deficiency anemia is highly prevalent amongst 12- to 23-month-old infants.

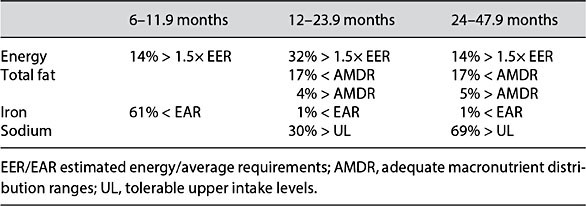

Table 2. Inadequate and excessive intakes of energy, total fat, iron, and sodium in the diets of infants and young children in Mexico

We also reported that 31 and 35% of 6- to 11.9-month-old infants consumed cow’s milk or sugar sweetened beverages, respectively [6]. According to Mexican and international guidelines [4], the only appropriate beverages for this age group would be breast milk, infant formula, and water. In children 12–23.9 months old, 63% consumed sweetened beverages. These included sweetened teas (23%) and traditional Mexican beverages (30%), such as atoles (hot beverages prepared with corn flour, milk or water, sugar, and flavorings), licuados (smoothie-type drinks made with milk, fruit, and ice), and aguas frescas (sweetened beverages prepared with fruit and water). Because of the fruit and milk content, these beverages also provide some nutrients important in the diets of children, but overconsumption would add additional energy that is not needed in an obesogenic environment [6].

Usual energy intakes of Mexican infants and toddlers (6–47.9 months) exceed estimated energy requirements in 14–32% of the population (Table 2). Iron intakes were low for 61% of infants 6–11.9 months old, who did not meet the estimated average requirement for iron, indicating a nutritional risk. About 5% of children 12 months and older exceeded the acceptable macronutrient distribution range for fat. More than 30% of toddlers exceeded their tolerable upper intake level for sodium [7].

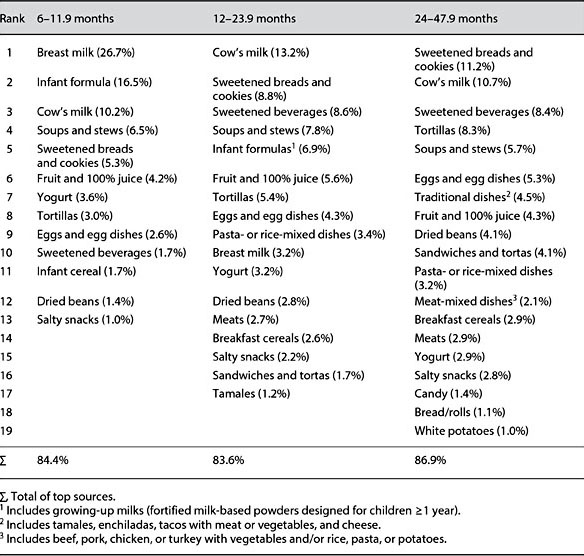

Table 3. Top food sources of energy (daily energy in %) in the diets of Mexican infants and young children

The extra energy has been linked to consumption of energy-dense foods low in micronutrients, including foods and beverages with added sugar and various maize-based preparations. In fact, sweetened breads and cookies, and sweetened beverages, including traditional beverages, sweetened teas, and fruit-flavored drinks, were among the top sources of energy for 12- to 23.9-month-old infants (Table 3). By the age of 24–47.9 months, the diversity of sweets expanded to include carbonated sodas and candy, along with sweetened breads and cookies, and various sweetened beverages. Overall, the top nutrient contributors in the diet were milk, soups and stews, eggs, egg dishes, and fruits. Tortillas, eggs, and egg dishes were among the top contributors of iron and zinc [8].

Findings from ENSANUT and from the FITS analysis specifically were used by a broad-country panel of experts to develop new feeding recommendations for healthy infants in Mexico [4]. The expert panel set new and more strict recommendations for child feeding. One of the recommendations had to do with the proportions of milk versus foods in the diets of infants and young children. They recommended that the diet of infants from 6 to 8 months should consist of approximately 60% breast milk and 40% solids. From 9 to 11.9 months, infants should be receiving about 53% of their diet as complementary food, and by 12 months, this increases to 62%. Whole cow’s milk should not be introduced until 12 months of age, because cow’s milk is low in iron. Iron sources of fortified infant cereal and meats should also be introduced to meet iron recommendations. Public policy must change accordingly.

Conclusion

Continuous study of feeding patterns in a population, especially in children, will be a powerful tool to monitor health and nutrition status of the whole country. Through the FITS research, we have found that 6-month exclusive breastfeeding is exceedingly low in Mexico. Even if 62% of 4- to 5.9-month-old infants receive some breast milk, many of the substitutes are not acceptable. We have seen early introduction of cow’s milk and various sweetened traditional and other beverages being consumed at young age. Another issue for infants is low consumption of iron-rich foods, such as fortified infant cereals and meat. Tortillas are fortified with iron in Mexico, but this does not address the low iron intakes for babies 6–11.9 months of age. Fruits were consumed by only about half of infants and young children, and vegetable consumption is even lower (around 20%). This, along with the pervasive consumption of sweets and sweetened beverages, shows that nutrient-rich foods are being displaced by higher-energy, low-nutrient-dense foods in the diets of Mexican children. Actions to address these issues have been taken in the form of the development of the Consensus on Complementary Feeding of Healthy Infants [4]. This serves as a call to action for pediatricians and other health care workers, but the recommendations still need to be widely implemented in practice.

References

-

1 Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Obesity Update 2017. http:// www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/Obesi- ty-Update-2017.pdf (accessed July 4, 2018).

-

2 Hernández-Cordero S, Cuevas-Nasu L, Morán-Ruán MC, et al: Overweight and obesity in Mexican children and adolescents during the last 25 years. Nutr Diabetes 2017; 7:e247.

-

3 De la Cruz-Góngora V, Villalpando S, Shamah-Levy T: Prevalence of anemia and consumption of iron-rich food groups in Mexican children and adolescents: ENSANUT MC 2016. Salud Pública Mex 2018;60:291–300.

-

4 Romero-Velarde E, Villalpando S, Pérez- Lizaur A, et al: Consenso para las prácticas de alimentación complementaria en lactantes sanos. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex 2016;73: 338–356.

-

5 Deming DM, Afeiche MC, Reidy KC, et al: Early feeding patterns among Mexican babies: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Survey 2012 and implications for health and obesity prevention. BMC Nutr 2015;1:40.

-

6 Afeiche MC, Villalpando-Carrion S, Reidy KC, et al: Many infants and young children are not compliant with Mexican and international complementary feeding recommendations for milk and other beverages. Nutrients 2018;10:E466.

-

7 Piernas C, Miles DR, Deming DM, et al: Estimating usual intakes mainly affects the micronutrient distribution among infants, toddlers and pre-schoolers from the 2012 Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey. Public Health Nutr 2016;19:1017– 1026.

-

8 Denney L, Afeiche MC, Eldridge AL, Villal- pando-Carrion S: Food sources of energy and nutrients in infants, toddlers, and young children from the Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey 2012. Nutrients 2017; 9:E494.

-

9 Romero-Martínez M, Shamah-Levy T, Fran- co-Núñez, et al: National health and nutrition survey 2012: design and coverage. Salud Pública Mex 2013;55:S332–S340.

-

10 Lopez-Olmedo N, Carriquiry AL, Rodriguez- Ramirez S, et al: Usual intake of added sugars and saturated fats is high while dietary fiber is low in the Mexican population. J Nutr 2016;146:1856S–1865S.

-

11 Devaney B, Ziegler P, Pac S, et al: Nutrient intakes of infants and toddlers. J Am Diet Assoc 2004;104:S14–S21.

-

12 Butte NF, Fox MK, Briefel RR, et al: Nutrient intakes of US infants, toddlers, and pre-schoolers meet or exceed dietary reference intakes. J Am Diet Assoc 2010;110:S27–S37.