Breakfast Consumption versus Breakfast Skipping: The Effect on Nutrient Intake, Weight, and Cognition

Abstract

Breakfast has long been promoted as the most important meal of the day. However, the lack of standard definitions of breakfast, breakfast consumers, and breakfast skippers, and the lack of a description of how “important” the meal is, especially compared with other meals, has hampered the ability to confirm this long-held belief. This review discusses potential definitions of breakfast and breakfast skippers, and how these definitions can affect how researchers, nutrition educators, and policy makers interpret data and make recommendations. Overall, breakfast, especially meals including ready-to-eat cereal, con- tributes to overall nutrient intake and diet quality. However, the association of breakfast consumption and weight parameters or cognition in children is controversial. Finally, challenges, opportunities, and research gaps with breakfast studies are discussed. The question of whether breakfast is the most important meal of the day remains unanswered.

Introduction

What do 朝ごはん, Frühstück, desayuno, almusal, aamiainen, bữa ăn sáng, səhər yeməyi, parakuihi, and lijo tsa hoseng have in common? They all mean breakfast – the meal that literally “breaks the fast.” But these terms mean something very different to the different cultures that use these words for the first meal of the day. In Japan, breakfast may consist of white rice, natto, fried eggs, tofu, miso soup, and tea. In Germany, cheese, meat (especially sausages), boiled eggs, fruit, and vegetables, smoked fish, and hearty, seeded breads with jam and honey are served. In Spain, breakfast is simply café con leche and a small roll or pastry. Even in countries using a common language, for example English, traditional breakfasts are different. In Great Britain, baked beans, black pudding, and grilled tomatoes are typical fare; however, these foods are seldom consumed for breakfast in the USA. As shown below in the nutrient intake and weight sections, within the USA, there is a wide variety of foods consumed at breakfast [1, 2].

For people living in different countries, when someone uses the local term for breakfast, there is a common understanding of what is meant. However, there is no standard definition for breakfast, for a nutritious breakfast, or for breakfast skipping. This is a problem for scientists looking at the effect of breakfast consumption on daily nutrient intake, weight, and other physiologic parameters, or cognition. The lack of any standard definition makes it difficult to interpret the literature.

A wide variety of definitions of breakfast and breakfast skipping has been used in the literature [3], including: “any energy-containing food or beverage (excludes water but not black tea/coffee) consumed between 5 a.m. and 9.30 a.m.,” “any food and/or beverage reported as consumed in the morning or for breakfast or desayuno (Spanish equivalent of breakfast), or brunch,” and “the first meal of the day, eaten before or at the start of daily activities, within 2 h of waking, typically no later than 10 a.m., and of a calorie level between 20 and 35% of total daily energy needs.” Definitions of breakfast skipping included “skip breakfast at least one time per week,” “skip breakfast at least six times per week,” and “not eating a morning meal at home.” These definitions, especially for the breakfast skippers, are at best inconsistent and at worst inappropriate. They also demonstrate how individuals can be placed into the wrong categories for statistical analysis in breakfast studies.

The majority of studies examining the effects of breakfast have been epidemiologic but not clinical trials. Results of any epidemiologic study will be greatly affected by these varying definitions for individual studies, since individuals can easily be placed in incorrect breakfast consumption/skipping groups for analysis. This alone could account for the conflicting results of research related to breakfast consumption [3]. Since it is so difficult to determine the effect of breakfast consumption on physiologic and behavioral parameters, the body of evidence, not an individual study, must be considered.

There is no formal recommendation for consuming breakfast, although the 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) [4] include breakfast meal patterns and the 2015–2020 DGA Advisory Committee (DGAC) [5] discusses the nutrient contribution of breakfast. This is a departure from the 2010 DGA, which recommended a “nutrient-dense” breakfast [6] – without actually defining one. Having neither a recommendation for consuming breakfast nor a standard definition has implications for researchers, nutrition educators, and policy makers [3, 7].

The lack of a standard definition also makes it difficult to answer the question: Is breakfast the most important meal of the day? How can we know this if we do not know what breakfast is? It is also unclear what is meant by “important” [8]. Important how: To nutrient contribution? To health and weight management? To cognition and school or work performance? These 3 questions are discussed below. But a key, unanswered question is: Has breakfast been adequately compared with other meals/snacks? And the answer to that question is no.

Nutrient Contribution of the Breakfast Meal

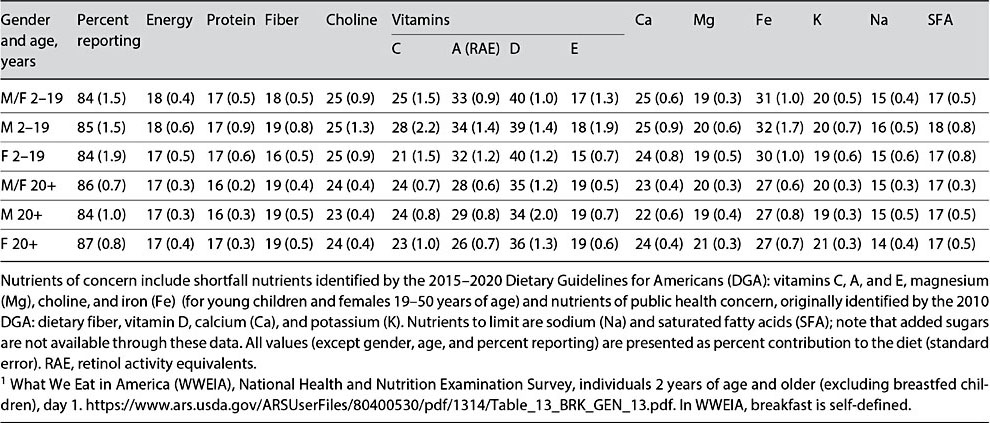

Data from What We Eat in America (WWEIA) 2013–2014 [9] show that dinner was the most consumed meal of the day, followed by breakfast and lunch; 86% of Americans 2 years of age and older consumed breakfast. Consumption of breakfast varied by age and gender with children 2–5 years of age having the highest levels of consumption, and adolescents (12–19 years) and young adults (20–29 years) the lowest levels. On average, breakfast has a higher overall diet quality because of its higher nutrient density compared to other meals and snacks. For children 2–19 years, breakfast supplied 18% of energy, 40% of the vitamin D recommendation, 25% of calcium, 31% of iron, and only 15% of the sodium recommendation. Breakfast supplies up to 33% of the recommendations for B vitamins. For nutrients to limit, breakfast supplies 17% of the daily intake of saturated fatty acids and 15% of sodium.

There is room for improvement in the nutrient intake at breakfast. The per- cent contribution of 3 of the 4 nutrients of public health concern (fiber, vitamin D, calcium, and potassium) – fiber (36%), calcium (29%), and potassium (35%) – was highest at the dinner meal. Many of these nutrients are found in foods, such as whole grains, dairy products, and fruit, which are commonly consumed at breakfast, suggesting an opportunity for encouraging consumption of these foods at breakfast. Only vitamin D intake (36%) was highest at breakfast. Break- fast supplied the lowest percentage intake of saturated fatty acids, and only snacks (14%) provided a lower intake of sodium. The average contribution of breakfast to energy, protein, shortfall nutrients, and nutrients to limit [5] to the American diet is shown in Table 1 [9].

Children who skipped breakfast have been shown to have lower intakes of fiber; vitamins A, E, C, B6, and B12; folate; iron; calcium; phosphorus; magnesium; and potassium [10]. Adults who skipped breakfast had lower intakes of all micronutrients examined except sodium [11]. Children [12] and adults [11] who skipped breakfast did not compensate for the nutrients missed at other meals.

Most of the articles that have examined the effect of breakfast consumption have considered only 2 categories – “breakfast” versus “no breakfast” – apparently assuming that all breakfast meals are created equally. Cho et al. [13], using data from NHANES III (the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey), suggested that different types of breakfast were associated with different health parameters, for example, weight. Those findings led to the examination of “types of breakfast” with different parameters, including nutrient intake [12, 14]. Using more recent data from NHANES, the mean adequacy ratio of 5 short- fall nutrients (i.e., vitamin E, calcium, magnesium, potassium, and fiber) and 13 micronutrients was lowest in breakfast skippers, followed by “other breakfast” consumers, and highest in ready-to-eat cereal (RTEC) consumers [12]. In that study, breakfast was self-defined and “other breakfasts” were not defined; pre-sweetened RTEC (PSRTEC) and RTEC were combined into a single category. Subsequently, it was shown that those consuming PSRTEC also had significantly higher nutrient intakes than those consuming “other breakfasts” [15].

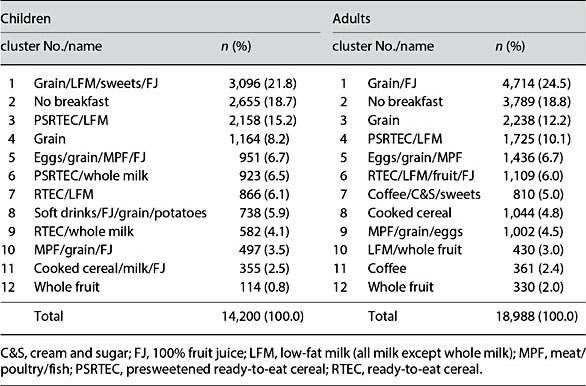

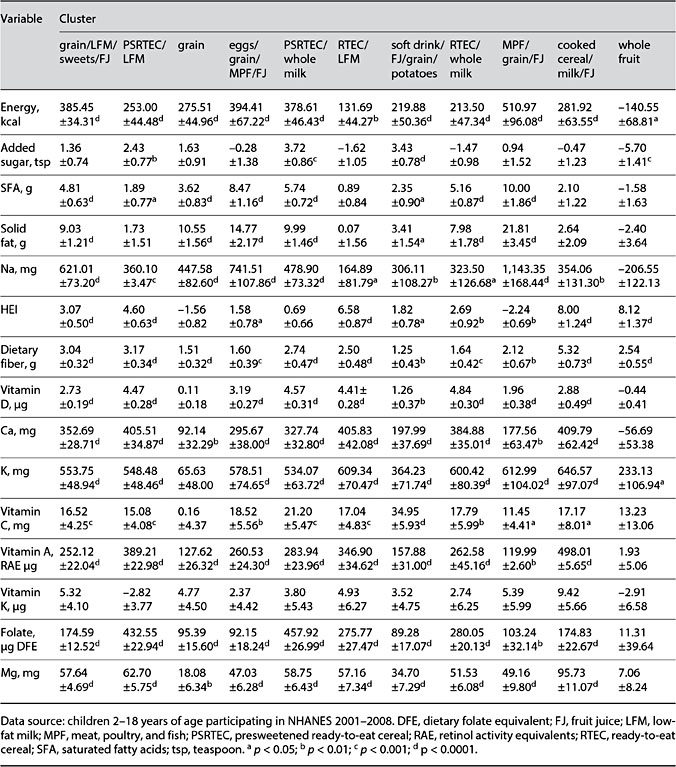

The nutrient contribution of breakfast patterns has been examined in children [1] and adults [2] participating in NHANES, thus helping to define “other breakfasts” and demonstrating the importance of examining what was actually consumed for breakfast. Twelve breakfast patterns, including no breakfast, were identified for children [1] and adults (Table 2) [2]. Placement into most breakfast patterns was associated with higher intakes of nutrients of public health concern; exceptions were: pattern 4 – fiber, vitamin D and calcium; patterns 5, 6, and 9 – fiber; pattern 8 – fiber and vitamin D; pattern 10 – fiber, vitamin D, calcium, and potassium; and pattern 12 – vitamin D and calcium. Assessment of diet quality, using the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) 2005, showed that children in patterns 1, 3, 7, 11, and 12 had higher diet quality and those consuming pat- tern 10 had a lower diet quality than those consuming no breakfast. Table 3 shows the β-coefficients for energy, nutrients to limit, shortfall nutrients, and the HEI scores for the breakfast patterns of children.

Adults [2] also showed significant differences in nutrient intake, but diet quality was perhaps the most interesting result of this study. Of the 12 breakfast patterns, only patterns 1, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 were associated with a higher diet quality than no breakfast. Breakfast patterns 5, 7, 9, and 11 were not different from no breakfast.

Together, the data from these studies clearly underscore the problem with understanding the association of nutrient intake and breakfast consumption when considering only the generic term “breakfast.” They also support the repeated finding that RTEC, including PSRTEC, consumption is associated with higher nutrient intake and diet quality.

Table 1. The contribution of energy, protein, nutrients of concern, and nutrients to limit from breakfast to the American diet in children and adults: What We Eat in America 2013–20141

Table 2. Breakfast clusters by name, number, and percent of consumers in children and adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: 2001–2008

Breakfast and Weight

A widely held belief among many health professionals is that consumption of breakfast is associated with lower weight; studies also suggest that consumption of breakfast also helps individuals lose weight or maintain a weight loss. So established were these beliefs that the 2010 DGA [6] recommended the public to “eat a nutrient-dense breakfast. Not eating breakfast has been associated with excess body weight, especially among children and adolescents. Consuming breakfast also has been associated with weight loss and weight loss maintenance, as well as improved nutrient intake.”

However, at the time of the 2015–2020 DGA [4], the recommendation had changed: “Healthy eating patterns can accommodate other nutrient-dense foods with small amounts of added sugars, such as whole-grain breakfast cereals or fat-free yogurt, as long as calories from added sugars do not exceed 10 percent per day, total carbohydrate intake remains within the AMDR, and total calorie intake remains within limits.” So, although there are comments about breakfast, there was no specific recommendation for consuming this mean or no recommendation regarding weight loss or maintenance.

Why the change in recommendations? For the most part, the study designs examining breakfast consumption and weight have been prospective cohorts or cross-sectional, where cause and effect cannot be determined. These studies, alone and when included as part of systematic reviews, have produced inconsistent results [3, 16, 17]. Recent clinical trials that have examined the association between breakfast consumption and weight have shown that body weights in the breakfast/no-breakfast groups were not different after 6 or 16 weeks [8, 18].

Many of the studies of breakfast consumption and weight have been hampered by the lack of a standard definition of breakfast, poor study design, small sample sizes, biased reporting of results, incorrect citing of the results of others, and inadequate control groups for the clinical trials [19]. The use of anecdotal evidence, such as that provided by the National Weight Control Registry, supporting the role of breakfast as a behavioral strategy for weight loss [20], does not add significantly to the body of literature.

One of the most important limitations in many of the articles has been the failure to include the type of breakfast consumed. As seen when evaluating the nutrient contribution of breakfast to total nutrients consumed, assessment of different types of breakfast meals may be important when looking at the effect that breakfast has on weight. Studies have shown that those consuming different breakfast meals, notably those containing RTEC, were significantly more likely to have lower body mass indices (BMIs) than those consuming other breakfasts or breakfast skippers [1–3, 12, 13].

Data from NHANES III were analyzed, and 10 breakfast categories were identified: skippers, meat/eggs, RTEC, cooked cereal, breads, quick breads, fruits/vegetables, dairy, fats/sweets, and beverages [13]. Those that were placed into the RTEC, cooked cereal, or quick bread patterns for breakfast had significantly lower BMIs than skippers and those in the meat/egg pattern. Skippers and fruit/vegetable eaters had the lowest daily energy intake. Those in the meat/egg pattern had the highest daily energy intake and one of the highest mean BMIs.

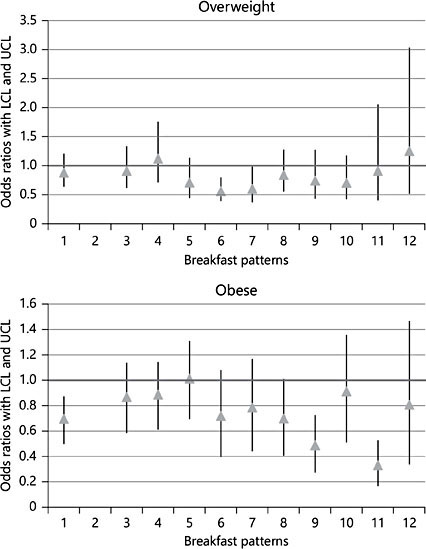

There are several ways to assess the association between breakfast consumption and weight parameters. For children, the likelihood that placement into a specific breakfast pattern [1], compared with no breakfast, was associated with a lower risk of overweight or obesity is shown in Figure 1. The risk of overweight was lower only in patterns 6 and 7. The risk of obesity was lower in patterns 1, 9, and 11. Although not shown graphically, the risk of overweight or obesity was lower for children placed in patterns 1, 6, 7, and 9, when compared with no breakfast. These data clearly show how combining all types of breakfast or limiting studies to RTEC and “other breakfast” can lead to inconsistent results.

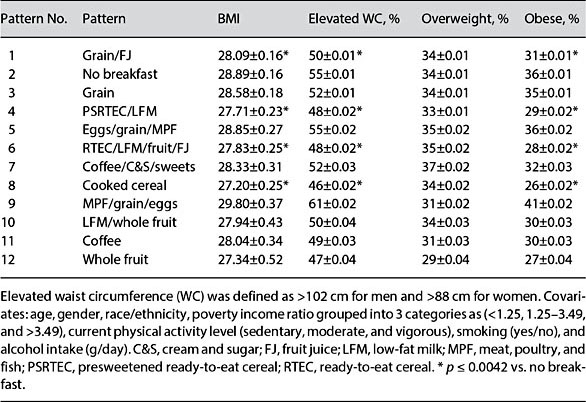

In adults [2], only those placed in patterns 1, 4, 6, and 8 had a lower mean BMI and percent elevated waist circumference than those consuming no breakfast; none of the breakfast patterns was associated with a higher mean BMI or percent elevated waist circumference than those consuming no breakfast (Table 4).

It is clear that the type of breakfast is important when assessing the effects of “breakfast consumption” on nutrient intake and weight parameters on consumers. It is critical that the type of breakfast be included in the evaluation of the effect of breakfast consumption on any health parameter, since the use of a “generic definition” can itself cause inconsistent results.

Table 3. Comparison of β-coefficients ± SE for energy, nutrients to limit, Healthy Eating Index (HEI), and shortfall nutrients by breakfast cluster compared with no breakfast (pattern 2) for children participating in NHANES 2001–2008

Fig. 1. The odds of children 2–18 years of age (n = 14,200) participating in NHANES 2001– 2008 being overweight or obese by breakfast consumption pattern: 1, grain/low-fat milk (LFM)/sweets/fruit juice (FJ); 2, no breakfast (comparison group); 3, presweetened ready- to-eat cereals (PSRTEC)/LFM; 4, grain; 5, eggs/grain/meat, poultry, fish (MPF)/FJ; 6, PSRTEC/ whole milk; 7, RTEC/LFM; 8, soft drinks/FJ/grain/potatoes; 9, RTEC/whole milk; 10, MPF/ grain/FJ; 11, cooked cereal/milk/FJ; 12, whole fruit; LCL, lower confidence limit; UCL, up- per confidence limit. p < 0.0042

Table 4. Weight parameters by breakfast pattern in adults ≥19 years of age participating in 2001–2008 NHANES (least-square means ± SE) (modified from O’Neil et al. [2]

Breakfast and Neuropsychological Functioning

Another benefit of breakfast consumption that has long been promulgated is improvement in cognitive performance in school-age children by improving memory, reaction time, vigilance, attention, problem-solving and arithmetic tasks, and logical reasoning. Systematic reviews have examined these relationships [21–24] as well as psychological processes [25]. In one recent systematic review [24], 45 studies in 43 articles were reported. The majority (n= 34) only considered the acute effect of a single breakfast meal, and performance was usually assessed within 4 h of breakfast. These studies compared results with breakfast skippers (n = 24) or with a comparison of different types of breakfast (n= 15). Although, breakfast consumption generally showed some short-term (i.e., same morning) positive associations with these outcomes, results were inconsistent across the cognitive domain and types of breakfasts consumed. Results also appeared to be strongest in children who were nutritionally vulnerable. Firm conclusions about the acute effects of specific breakfast types were unable to be drawn [24]. Subsequent work by these authors reviewed methodological challenges associated with these types of studies [26].

From a systematic review on the effects of breakfast and breakfast composition on cognition in children and adolescents, firm conclusions could not be drawn since there were too few studies, and findings were inconsistent [24]. “Seven of the eight studies of chronic consumption of breakfast demonstrated equivocal findings for attention in both well- and under-nourished children” [24].

Many of the acute studies [24] had serious design flaws, limiting their generalizability. These included small sample sizes; overrepresentation of certain age groups; artificial situations with a lack of an ad libitum breakfast meal; and laboratory-based studies rather than school-based studies. A number of physiologic mechanisms that may have affected the test results were explored; however, there are many other reasons on how children perform on tests. These include innate ability, acute or chronic illness, sleep amount/quality before the tests, interest in school or the test, current mood, and learning disabilities. Other outside influences include exposure to parental discord or neglect, lack of investment in the child, e.g., they do not read to the child; low socioeconomic status; and English may not be the child’s first language, to low-achieving schools.

It is important to design studies that are sufficiently powered with power calculations based on actual effect sizes; that are more field based; that have more realistic ad libitum breakfasts, and that use cognitive function tests with proven sensitivity that cover a variety of cognitive domains [24] to understand the potential relation of breakfast consumption and cognitive performance. A recent rigidly controlled crossover clinical trial with a repeated-measure design was conducted in children 8–10 years of age [27]. Participants were rigidly screened and excluded if they were obese; had a history of learning disabilities, sensory impairments, mood disorders, acute or chronic disease, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; or were taking medications. The study was powered at 80%.

Children (n = 128) were admitted to a metabolic research unit 15 h before the morning experimental procedures began. They were subjected to a physical examination, screened for conditions that could affect test results, and fed 1 of 2 isocaloric dinners. A predetermined Latin-square design for assignment of the 6 possible sequences of the 3 different treatments was used: no breakfast and 1 of 2 similar breakfast options. After spending the night in the metabolic research unit, participants had preprandial serum glucose and ketone levels measured to ensure the child could continue with the test. Children were fed a breakfast or given no breakfast at a specific time and underwent a battery of neuropsychological tests, including measures of attention, impulsivity, short-term memory, cognitive processing speed, and verbal learning 2 h later. There were no significant differences seen in children who consumed breakfast or did not for any of the neuropsychological measures administered. Thus, this carefully conducted study showed that breakfast consumption had no short-term effect on neuropsychological functioning in healthy school-age children. More of these studies, along with studies of habitual breakfast consumption, are needed to confirm and extend these results [26].

Challenges, Opportunities, and Research Gaps with Breakfast Studies

Making any type of widespread statement about breakfast and any potential benefits is severely hampered by the lack of a standard definition of breakfast. This has been cited repeatedly as a limitation to individual studies examining the effect that breakfast has on nutrient intake and health, but it is also a major problem when trying to interpret systematic review articles or meta-analyses. For nutrition educators or policy makers, it is difficult to know what the best foods to recommend are and what the best times to serve them are. Should “breakfast,” a term that most individuals understand implicitly, as it relates to their culture, be defined using groups of foods, or by a specific energy, macronutrient, or micronutrient prescription? These elements have been suggested as definitions of a quality breakfast [3], a nutrient-dense breakfast [6], or an ideal breakfast [28].

Should the definition of breakfast be forced into a time frame? Many of the proposed definitions fall into an arbitrary time frame that may not fit the needs of all, notably the millions of individuals who work the evening or night shifts or others with erratic work or school schedules [3]. Equally, should the definition be dictated as to place? One of the definitions given earlier in this paper for breakfast skippers considered only breakfast consumed at home. This eliminates as consumers the more than 14 million children who participate in the School Breakfast Program [29] and those children and adults consuming breakfasts away from home.

Finally, when considering if breakfast is the most important meal of the day, the effects need to be compared with those of other meals. While the nutrient contribution of other meals is available through WWEIA [9], an intensive study of lunch and dinner meals as they are linked to weight and cognition has not been conducted.

Conclusion

Foods consumed at the breakfast meal are culturally different, but to most individuals, when they hear the local word for “breakfast,” it is understood what is meant. However, for researchers, nutrition educators, and nutrition policy makers, there is no standard definition of breakfast, breakfast consumers, or breakfast skippers. This hinders interpretation of individual articles and makes it difficult to compare the literature. It has also led to conflicting results, compounding the difficulty for educators and policy makers to make recommendations for what to consume at breakfast.

Breakfast has also been heralded as the “most important meal of the day,” not only because it is for most people the first major eating episode after the longest period without eating, but because it has been championed as a meal that contributes significantly to nutrient intake, can be used to lose weight or maintain a weight loss, and can improve cognition and school performance in children. But is it the most important meal? There are two considerations here: What does “important” mean? Again, there is no definition. Further, how does the contribution of the breakfast meal to nutrient intake, weight management, or cognition compare with other meals and snacks? Breakfast has been intensively studied – lunch, dinner, and snacks, less so.

How breakfast consumption or breakfast skipping is defined influences the results of studies. In general, nutrient intake and diet quality are better if breakfast is consumed. Weight and weight management also depend on the type of breakfast consumed. It has been demonstrated clearly that the type of breakfast consumed affects nutrient intake, diet quality, and weight; therefore, a simple definition of “breakfast” does not significantly add to the literature. Less well defined is the role breakfast plays in the cognition of students. Although accepted as fact, results evaluating acute and chronic consumption of breakfast and cognition are equivocal. Systematic reviews and a carefully conducted clinical trial have suggested that there is no association between consumption of breakfast and cognition in school-age children.

More carefully controlled studies that use a standardized definition of break- fast consumption and breakfast skipping are needed to determine the effects on nutrient intake, health parameters, and academic performance. In addition, equivalent studies of the lunch and dinner meals are needed, before it can be determined if “breakfast is the most important meal of the day.”

References

- 1 O’Neil CE, Nicklas TA, Fulgoni VL 3rd: Nutrient Intake, diet quality, and weight measures in breakfast patterns consumed by children compared with breakfast skippers: NHANES 2001–2008. AIMS Public Health 2015;2:441–468.

- 2 O’Neil CE, Nicklas TA, Fulgoni VL 3rd: Nutrient intake, diet quality, and weight/adiposity parameters in breakfast patterns compared with no breakfast in adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2008. J Acad Nutr Diet 2014;114(12 suppl):S27–S43.

- 3 O’Neil CE, Byrd-Bredbenner C, Hayes D, et al: The role of breakfast in health: definition and criteria for a quality breakfast. J Acad Nutr Diet 2014;114(12 suppl):S8–S26.

- 4 Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015–2020. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/ guidelines (accessed February 10, 2018).

- 5 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee Re- port 2015–2020. https://health.gov/ dietaryguidelines/2015-scientific-report/ PDFs/Scientific-Report-of-the-2015-Dietary- Guidelines-Advisory-Committee.pdf (accessed February 10, 2018).

- 6 Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2010/ dietaryguidelines2010.pdf (accessed February 10, 2018).

- 7 Frank GC: Breakfast: what does it mean? Am J Lifestyle Med 2009;3:160–163.

- 8 Betts JA, Chowdhury EA, Gonzalez JT, et al: Is breakfast the most important meal of the day? Proc Nutr Soc 2016;75:464–474.

- 9 United States Department of Agriculture. Ag- ricultural Research Service. What We Eat in America. https://www.ars.usda.gov/north- east-area/beltsville-md/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/food-surveys-re- search-group/docs/wweia-data-tables (accessed February 10, 2018).

- 10 Nicklas TA, Reger C, Myers L, et al: Breakfast consumption with and without vitamin-mineral supplement use favorably impacts daily nutrient intake of ninth-grade students. J Ad- olescHealth 2000;27:314–321.

- 11 Kerver JM, Yang EJ, Obayashi S, et al: Meal and snack patterns are associated with dietary intake of energy and nutrients in US adults. J Am Diet Assoc 2006;106:46–53.

- 12 Deshmukh-Taskar PR, Nicklas TA, O’Neil CE, et al: The relationship of breakfast skip- ping and type of breakfast consumption with nutrient intake and weight status in children and adolescents: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2006. J Am DietAssoc 2010;110:869–878.

- 13 Cho S, Dietrich M, Brown CJ, et al: The effect of breakfast type on total daily energy intake and body mass index: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Am Coll Nutr 2003; 22:296–302.

- 14 Priebe MG, McMonagle JR: Effects of ready- to-eat-cereals on key nutritional and health outcomes: a systematic review. PLoS One 2016;11:e0164931.

- 15 O’Neil CE, Zanovec M, Nicklas TA, et al: Presweetened and nonpresweetened ready- to-eat cereals at breakfast are associated with improved nutrient intake but not with in- creased body weight of children and adolescents: NHANES 1999–2002. Am J Lifestyle Med 2012;6:63–74.

- 16 Nooyens AC, Visscher TL, Schuit AJ, et al: Effects of retirement on lifestyle in relation to changes in weight and waist circumference in Dutch men: a prospective study. Public Health Nutr 2005;8:1266–1274.

- 17 Crossman A, Anne Sullivan D, Benin M: The family environment and American adoles- cents’ risk of obesity as young adults. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:2255–2267.

- 18 Dhurandhar EJ, Dawson J, Alcorn A, et al: The effectiveness of breakfast recommendations on weight loss: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;100:507–513.

- 19 Brown AW, Bohan Brown MM, Allison DB: Belief beyond the evidence: using the pro- posed effect of breakfast on obesity to show 2 practices that distort scientific evidence. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;98:1298–1308.

- 20 Wyatt HR, Grunwald GK, Mosca CL, et al: Long-term weight loss and breakfast in subjects in the National Weight Control Registry. Obes Res 2002;10:78–82.

- 21 Hoyland A, Dye L, Lawton CL: A systematic review of the effect of breakfast on the cognitive performance of children and adolescents. Nutr Res Rev 2009;22:220–243.

- 22 Rampersaud GC, Pereira MA, Girard BL, et al: Breakfast habits, nutritional status, body weight, and academic performance in children and adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc 2005; 105:743–760.

- 23 Edefonti V, Rosato V, Parpinel M, et al: The effect of breakfast composition and energy contribution on cognitive and academic performance: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;100:626–656.

- 24 Adolphus K, Lawton CL, Champ CL, et al: The effects of breakfast and breakfast composition on cognition in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Adv Nutr 2016;7: 590S–612S.

- 25 Adolphus K, Lawton CL, Dye L: The effects of breakfast on behavior and academic performance in children and adolescents. Front Hum Neurosci 2013;7:425.

- 26 Adolphus K, Bellissimo N, Lawton CL, et al: Methodological challenges in studies examining the effects of breakfast on cognitive performance and appetite in children and adolescents. Adv Nutr 2017;8:184S–196S.

- 27 Iovino I, Stuff J, Liu Y, et al: Breakfast consumption has no effect on neuropsychologi- cal functioning in children: a repeated-measures clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2016;104: 715–721.

- 28 Giovannini M, Verduci E, Scaglioni S, et al: Breakfast: a good habit, not a repetitive custom. J Int Med Res 2008;36:613–624.

- 29 School Breakfast Program. https://www.ers. usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/ child-nutrition-programs/school-breakfast- program (accessed February 10, 2018).