Complementary Feeding and Immunity

Section of Allergy, Children’s Hospital

Colorado, Aurora, CO, USA

david.fleischer@childrenscolorado.org

- Data from a randomized controlled trial that studied the timing of peanut introduction and peanut allergy outcomes clearly demonstrate that peanut allergy can be prevented by earlier introduction of peanut into an infant’s diet. While more randomized controlled trials are under way, the message that earlier introduction of highly allergenic foods can prevent food allergy needs to be communicated to medical providers around the world who care for infants.

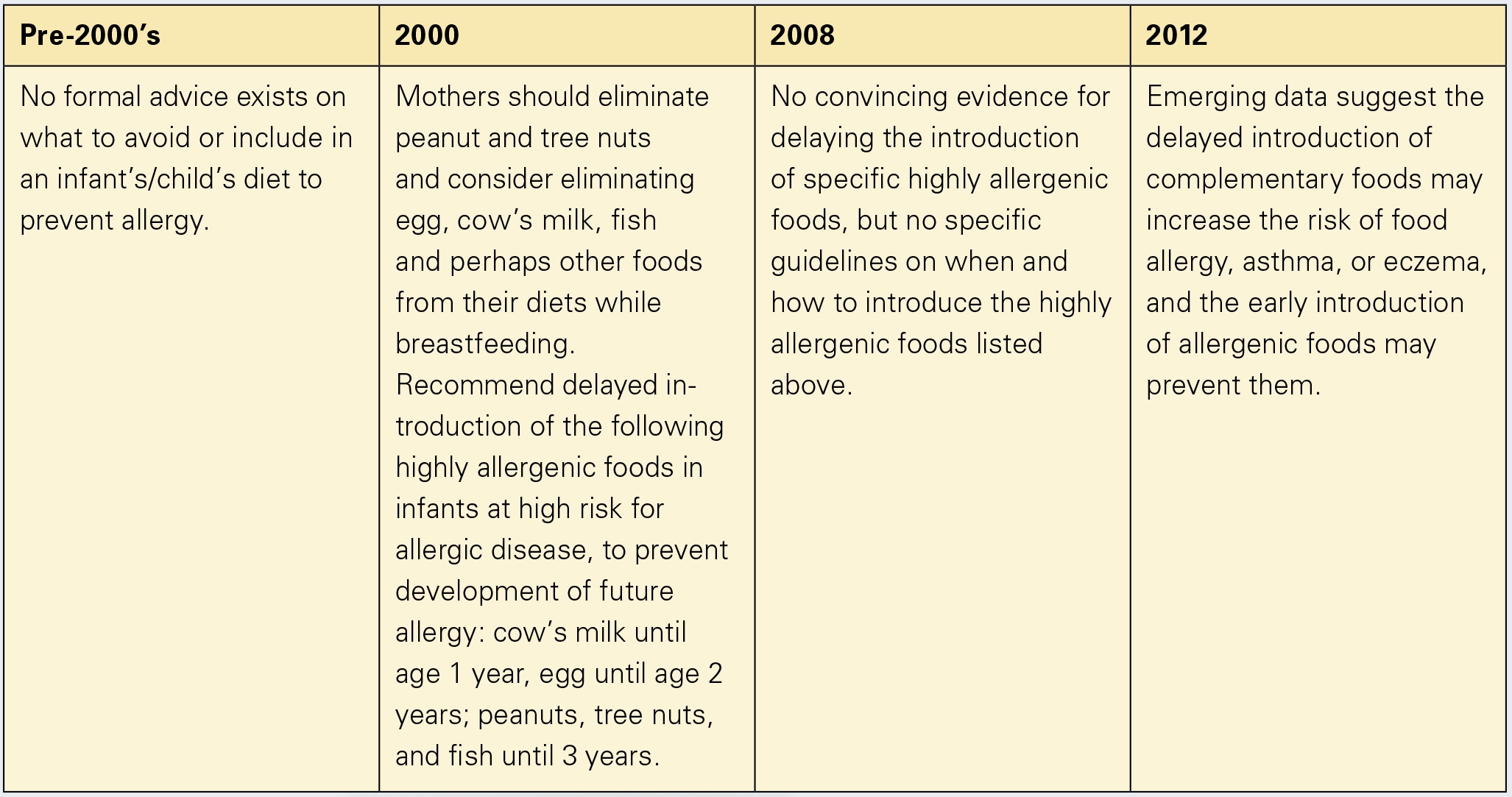

The correct age to introduce complementary food that will result in oral tolerance has been debated for decades (fig. 1). Recommendations to delay introduction of allergenic foods such as milk, egg, and peanut were made in 2000 [1] but then retracted in 2008 [2]; both statements were based on sparse firm data. Over the last several years, though, observational studies demonstrated that earlier introduction of highly allergenic foods might prevent the onset of allergies to them [3–5]. Recently, the landmark study Learning Early About Peanut (LEAP) was published [6]. LEAP is the first large randomized controlled trial (RCT) to investigate the timing of peanut introduction.

LEAP was performed in the UK in a cohort of 640 high-risk infants, defined as having severe eczema and/or egg allergy, who were randomized either to peanut introduction early between the age of 4–11 months versus peanut avoidance until the age of 5 years. At study entry, 542 infants had negative skin prick tests (SPT) to peanut, while 98 infants had SPT wheal diameters between 1 and 4 mm (minimally SPT positive). A total of 76 children were excluded prior to randomization based on a peanut SPT >5 mm and were presumed peanut-allergic. After 5 years of peanut protein consumption of 2 g thrice weekly or avoidance, food challenges were performed. An intention-to-treat analysis showed that 17.2% of the children in the peanut avoidance group compared to 3.2% of the children in the peanut consumption group developed food challenge-proven peanut allergy, corresponding to a 14% absolute risk reduction and a relative risk reduction of 80%.

Based on these LEAP data, allergy, pediatric, and dermatology organizations from around the world formulated a consensus statement that recommended early introduction of peanut (between 4 and 11 months of age) into the diet of high-risk infants in countries where peanut allergy is prevalent in order to prevent peanut allergy [7]. The organizations further recommended that certain high-risk infants, such as those with early-onset severe eczema or IgE-mediated food allergy, might benefit from evaluation to diagnose possible food allergy prior to peanut introduction. The National Institutes of Health and an expert panel are developing more formal guidelines for peanut allergy prevention.

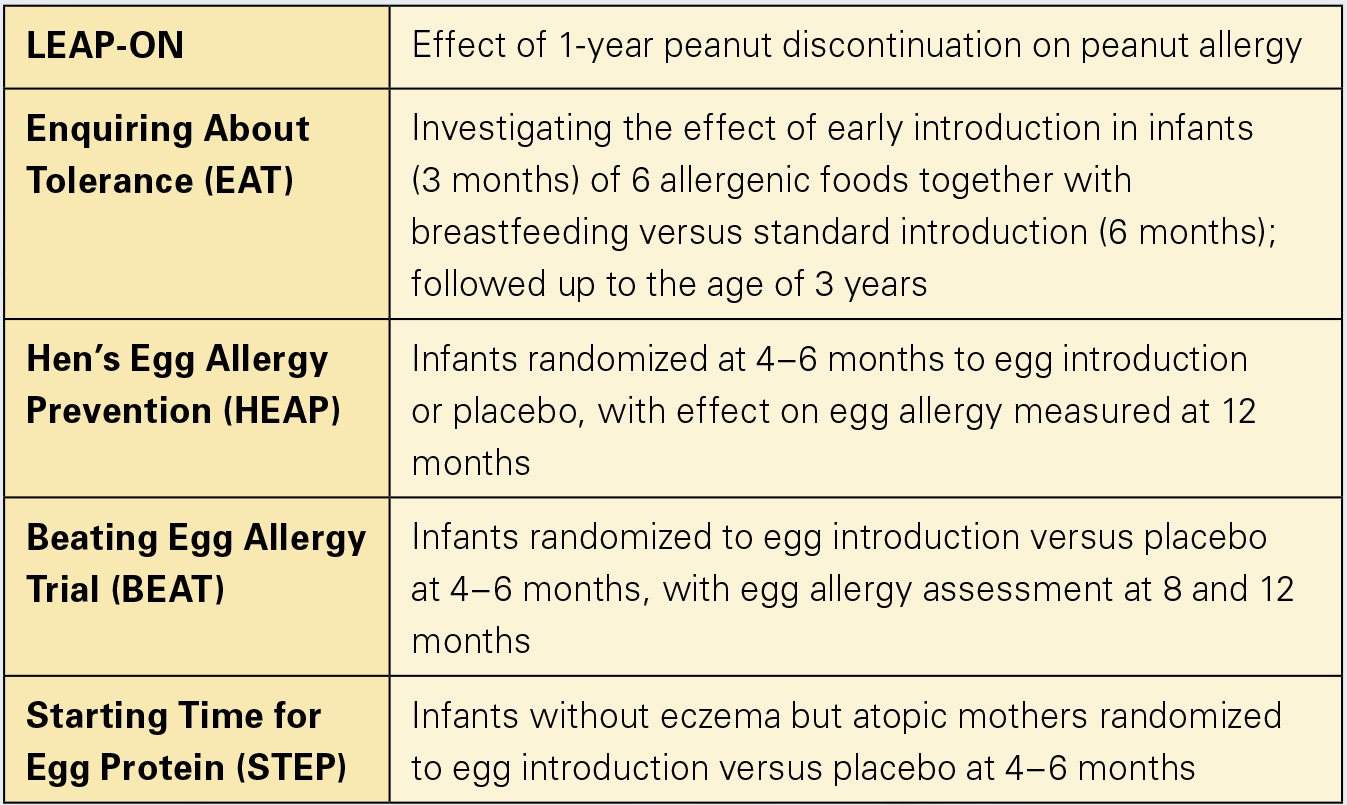

More RCTs investigating early versus delayed food introduction will be published in the coming years that will shine light on other major food allergens (table 1), as the specific time for introduction may be different for different foods and at-risk patients. A clear paradigm shift, though, has occurred, now backed by data, that earlier complementary food introduction is better for allergy prevention.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics 2000;106:346–349.

- Greer FR, Sicherer SH, Burks AW; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition, American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Allergy and Immunology: Effects of early nutritional interventions on the development of atopic disease in infants and children: the role of maternal dietary restriction, breastfeeding, timing of introduction of complementary foods, and hydrolyzed formulas. Pediatrics 2008;121: 183–191.

- Du Toit G, Katz Y, Sasieni P, Mesher D, Maleki SJ, Fisher HR, et al: Early consumption of peanuts in infancy is associated with a low prevalence of peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;122:984–991.

- Koplin JJ, Osborne NJ, Wake M, Martin PE, Gurrin LC, Robinson MN, et al: Can early introduction of egg prevent egg allergy in infants? A population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;126:807–813.

- Katz Y, Rajuan N, Goldberg MR, Eisenberg E, Heyman E, Cohen A, et al: Early exposure to cow’s milk protein is protective against IgE-mediated cow’s milk protein allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;126:77.e1–82.e1.

- Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, Bahnson HT, Radulovic S, Santos AF, et al: Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med 2015;372: 803–813.

- Fleischer DM, Sicherer S, Greenhawt M, Campbell D, Chan E, Muraro A, et al: Consensus communication on early peanut introduction and the prevention of peanut allergy in high-risk infants. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;136:258–261.