Geography and economics of obesity

For a long time, obesity research has focused on the quality of a person’s diet and which foods and drinks to avoid to prevent obesity. This is an intuitive approach, but it may surprise you to learn that what we eat and drink is actually a relatively weak predictor of obesity. It is not necessarily the case that a person with a poor-quality, high-calorie diet (lots of carbohydrates, added sugar, salt and vegetable oils) is more likely to become obese than someone who eats plenty of lean meats, fruits and vegetables. Part of the reason for this is that any study of diet quality relies on and is limited by how well participants are able to recall their food and drink consumption. As a scientific measure, it is simply not up to the task.

Where we live and who we are shapes our food choices

The next generation of obesity research needs to recognize that the responsibility for obesity falls on a person’s whole lifestyle. While healthy eating is certainly to be encouraged, the blame cannot be placed on any particular group of foods or beverages. I propose that it is where we live and who we are that has the greatest influence on our choices and consumption, and that this influence is subject to deep social and economic roots that often get overlooked when we talk about the causes of obesity.

By tending to focus on broad geographical areas, estimates of obesity can mask the true influence of social and economic differences on diet and behavior. In the USA, state-level and even county-level data can be misleading. What we need is to ‘drill down’ further and look in detail at what is really going on at the roots. Five years ago this would not have been possible, but recent advances in data analysis have allowed us to study obesity geography as never before.

By looking at health data in small areas called ‘census tracts’ (developed for the purposes of collecting national census data), we are able to identify obesity problems at a neighborhood level. Education and household income have been widely studied as predictors of obesity, but in Seattle, where I live, we discovered that 30% of the statistical differences in obesity across neighborhoods could not be explained by these two predictors alone.

Social standing and social class are connected to attitudes, and it is these attitudes that influence how we eat, where we buy our food, how we educate ourselves about food, and many other factors. So when we think about obesity, we need to start looking beyond food and income and start looking at the areas where people live, what they do, how they travel to work, where their children go to school, and so on.

Mapping obesity: what have property values got to do with it?

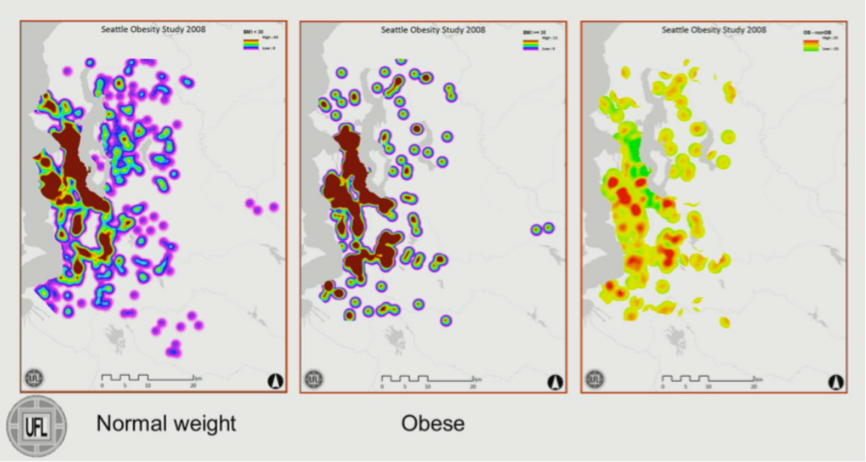

What we did in the Seattle Obesity Study was to ‘geocode’ the addresses of people’s homes, their workplaces, and the supermarkets they shopped at. In doing so, we were able to produce groundbreaking maps of obesity hotspots or ‘clusters’ that show where obesity was most common, without the restriction of geographic boundaries (Figure 1).1

Figure 1. Obesity hotspots in the Seattle Obesity Study

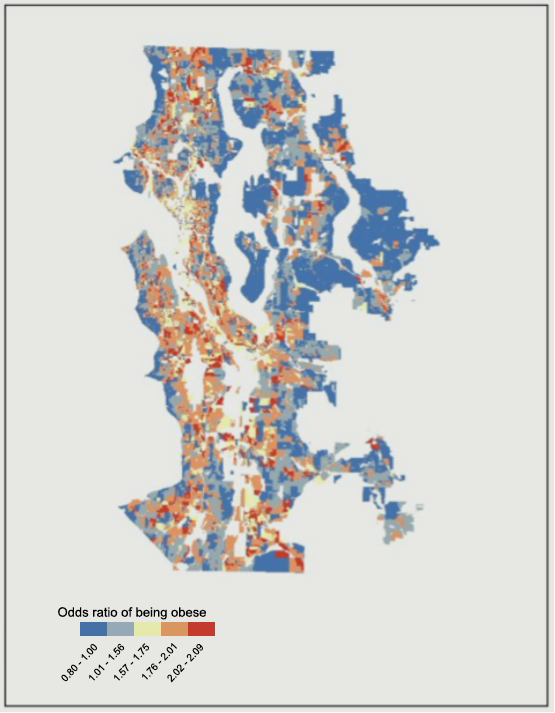

By combining techniques used in market and health research, we were able to show that the pattern of obesity across neighborhood blocks very closely matched the differences in property values (Figure 2). This finding potentially casts other theories for obesity (for example, genetics) in a new light.

Figure 2. Obesity mapping shows a strong association between obesity and property values

Using these mapping techniques, it is possible to develop an atlas of diet and health – a form of ‘nutritional landscaping’ that can be applied worldwide. This knowledge has allowed us to explore some of the social and economic reasons for obesity in more detail. By tracking people’s supermarket choices, we showed that so-called ‘food deserts’ – local areas where healthy food choices are hard to find – are not the most reliable predictor of obesity. We found that the cost of food was a stronger predictor of obesity than how far you have to travel to buy it.2 This is not so surprising, given that cheap calories tend to be low in nutrients and that nutrient-rich foods are often a lot more expensive per 100 calories (kcal).

Women’s weight is more closely linked to social and economic status

Thinking on a global scale, there are lessons to be learned from looking at the growing prevalence of obesity in developing societies, such as China, Vietnam and parts of India. Here, we are finding that it is the relatively rich people in urban centers rather than the urban poor that are becoming overweight and obese. Interestingly, though, when a country reaches a certain threshold of national wealth the distribution of obesity flips.3 In both scenarios, however, the impact of obesity is seen more among women than among men. It tends to be the women whose weight goes up as a society becomes richer, and it is women whose weight stays high as their neighborhoods become poorer.

Key references:

1. Drewnowski A, Rehm CD, Arterburn D. The geographic distribution of obesity by census tract among 59 767 insured adults in King County, WA. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013 Sep 16. [Epub ahead of print]

2. Drewnowski A, Aggarwal A, Hurvitz PM, et al. Obesity and supermarket access: proximity or price? Am J Public Health. 2012 Aug;102(8):e74-80.

3. Monteiro CA, Conde WL, Popkin BM. Income-specific trends in obesity in Brazil: 1975-2003. Am J Public Health. 2007 Oct;97(10):1808-12.

To watch the full presentation, click here

If you liked this post you may also like

Nestlé International Nutrition Symposium (NINS) - Nutrition, Obesity & Society

Relation of Eating Behaviour and Obesity

Obesity Treatment and Prevention: New Directions' to the topic

See our other experts opinion