Overnutrition: Does Complementary Feeding Play a Role?

Key Messages

- Specific risk parameters pertaining to complementary feeding are not firmly established for childhood obesity.

- Early introduction of complementary feeds, excess nutritional value of the feeds, and nonadherence to feeding guidelines may be associated with adult obesity.

Keywords

Obesity · Complementary feeding · Weaning · Exclusive breastfeeding · Nutrition

Abstract

Globally, obesity is considered an epidemic due to an increase in its prevalence and severity especially among young children and adolescents. This nutritional disorder is not limited to affluent countries as it is becoming increasingly prevalent in developing countries. Obesity is associated not only with cardiovascular, endocrine, gastrointestinal, orthopedic, and respiratory diseases, but also with psychological complications, implying a problem of far-reaching consequences for health and health services. Recently, evidence-based studies have shown that the duration of exclusive breastfeeding and the type of complementary feeds during the weaning period of an infant may have an effect on overnutrition later on in life. Thus, stemming the tide of obesity early on in life would potentially decrease the prevalence and complications of adult obesity, which could have significant implications for health care and the economy at large. This review explores the role of complementary feeding in obesity and approaches to prevention and treatment of childhood obesity by summarizing key systematic reviews. In conclusion, we found that although the relationship between complementary feeding and childhood obesity has been suspected for a long time, specific risk parameters are not as firmly established. Early introduction of complementary feeds (before the 4th month of life), high protein and energy content of feeds, and nonadherence to feeding guidelines may be associated with overweight and obesity later in life.

Introduction

Globally, obesity is being considered an epidemic due to an increase in its prevalence and severity especially among young children and adolescents. About 41 million 5-year-old children were obese worldwide in 2016 [1, 2] , with rapid rises in prevalence in many countries across the globe, especially in the developing world where the rate of increase is 30% higher than in developed countries [2, 3] . In Africa alone, the number of overweight children increased by 50% from the early 2000s [2] . Its association not only with cardiovascular, endocrine, gastrointestinal, orthopedic, and respiratory diseases, but also with all kinds of psychological complications, implies a problem of far-reaching consequences for health and health services, placing a huge economic burden to the individual and society at large [1, 2].

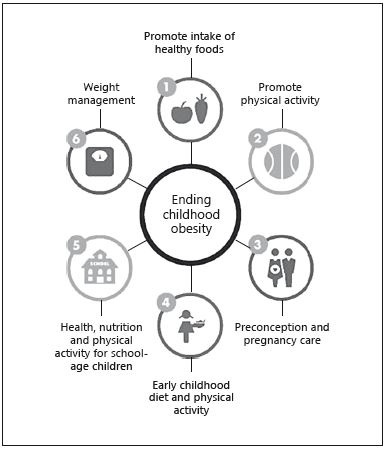

Obesity is mainly attributed to increased caloric intake and reduced physical activity. Other risk factors include high birth weight, rapid weight gain during infancy, firstborn children, being an only child, low socioeconomic status, lower level of parental education, parental obesity, and maternal smoking during pregnancy [4–7] . Recently, studies have also shown that the period of introduction and the type of complementary feeds during the weaning period of an infant may have an effect on overnutrition later on in life [8–10] . The WHO commission on Ending Childhood Obesity recommends exclusive breastfeeding till the age of 6 months, and thereafter, introduction of nutritious, safe, and appropriate complementary foods [2]. Figure 1 shows the six main recommendations from the WHO report on the Commission for Ending Childhood Obesity [2] .

Since a third of obese preschool- and half of obese schoolchildren remain obese in adulthood, early prevention and health promotion interventions are necessary to reduce the large number of overweight and obese adults, as well contribute to decreasing morbidity and mortality in adult age [1, 2].

This review scientifically explores the role of complementary feeding in obesity and approaches to prevention and treatment of childhood obesity.

Review of Evidence

Pearce et al. [8] from the University of Nottingham conducted a systematic review on the timing of the introduction of complementary feeding and the risk of childhood obesity. In keeping with the strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, data extracted from 23 studies were analyzed using an adapted Newcastle-Ottawa scale. Out of these 23 studies, 21 were able to demonstrate a relationship between the time at which complementary foods were introduced and childhood body mass index (BMI). Five of those found that introducing complementary foods at < 3 months (2 studies), 4 months (2 studies), or 20 weeks (1 study) was associated with a higher BMI in childhood. Seven of the studies considered the association between complementary feeding and body composition, but only 1 reported an increase in the percentage of body fat among children given complementary foods before 15 weeks of age. In conclusion, the systematic review revealed no clear association between the timing of the introduction of complementary foods and childhood overweight or obesity, but some evidence suggested that very early introduction (at or before 4 months), rather than at 4–6 months or > 6 months, may increase the risk of childhood obesity.

The same team of researchers also conducted a systematic review of the literature on the relationship between types of food consumed by infants during the complementary feeding period and overweight or obesity during childhood. Electronic databases were identified from inception until June 2012. Following the application of strict inclusion/exclusion criteria, 10 studies were identified and reviewed and data extracted using an adapted Newcastle-Ottawa scale to assess the quality of nonrandomized studies. The studies were then categorized into 3 groups: macronutrient intake, food type/group, and adherence to dietary guidelines. Some association was found between high protein intakes at 2–12 months of age and higher BMI or body fatness in childhood. Higher energy intake during complementary feeding was associated with higher BMI in childhood. Adherence to dietary guidelines during weaning was associated with a higher lean mass, but consuming specific foods or food groups made no difference to children’s BMI. They concluded that high intakes of energy and protein, particularly dairy protein, in infancy could be associated with an increase in BMI and body fatness, but further research was needed to establish the nature of the relationship. Adherence to dietary guidelines during weaning was recommended.

Jiangan Maternal and Child Health Hospital in Hubei, China, in conjunction with the Department of Food and Nutrition and the Medical College Huazhong University of Science and Technology, conducted a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies investigating whether the introduction of complementary feeding before 4 months of age increases the risk of childhood overweight or obesity [9]. Systematic reviews of articles published in PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane prior to March 2015 were identified. Ten articles consisting of 13 studies were identified, with 8 measuring being overweight as an outcome while 5 measured obesity. There were a total of 63,605 participants and 11,900 incident cases in the overweight studies, and 56,136 individuals and 3,246 incident cases in the obesity studies. The pooled results revealed that introducing complementary foods before 4 months of age compared to at 4–6 months was associated with an increased risk of being overweight (RR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.06–

1.31) or obese (RR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.07–1.64) during childhood. Of note, there was no significant relationship observed between delaying introduction of complementary foods after 6 months of age and being overweight (RR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.90–1.13) or obese (RR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.91–1.14). In conclusion, the study revealed that the introduction of complementary foods to infants before 4 months of age should be avoided to protect against childhood obesity.

Fig. 1. The six main recommendations of the WHO report on the Commission for Ending Childhood Obesity [2] .

In 2010, Seach et al. [11] tried to determine the association between infant feeding practices and childhood overweight/obesity. 620 subjects were recruited antena-tally from 1990 to 1994. A total of 18 telephone interviews over the first 2 years of life recorded infant feeding practices. At the mean age of 10 years, height and weight were measured for 307 subjects. Multiple logistic regression was used to determine whether infant feeding practices (duration of exclusive and any breastfeeding, and age at introduction of solid foods) were associated with odds of being overweight/obese (internationally age- and sex-standardized BMI category) at age 10 years, after adjustment for confounders. The results demonstrated that a delay in the introduction of solid foods was associated with reduced odds of being overweight/obese at age 10 years, after controlling for socioeconomic status, parental smoking, and childcare attendance (adjusted odds ratio, 0.903 per week; 95% CI, 0.841–0.970; p = 0.005). The duration of exclusive or any breastfeeding was not associated with the outcome.

Though some studies have shown an association between complementary feeding and obesity, others have been able to determine that there is no correlation with the timing of the introduction of complementary feeds.

Burdette et al. [12] tried to establish whether adiposity at 5 years of age was related to breastfeeding and timing of complementary feeding introduction using absorptiometry (DXA). Body composition was measured in 313 children at 5 years of age by using DXA. Data on breastfeeding, formula feeding, and timing of the introduction of complementary foods were obtained from the mothers when the children were 3 years old. Regression analysis was used to examine the relation between infant feeding and fat mass after adjustment for lean body mass, sex, birth weight, maternal obesity, race, and other sociodemographic variables. The study revealed that children who were breastfed for a longer duration and those who were breastfed without concurrent formula feeding did not have a significantly lower fat mass than those children who were never breastfed. Children did not differ significantly in fat mass if they were introduced to complementary foods before or after 4 months of age (4.49 ± 0.12 and 4.63 ± 0.12 kg, respectively; p = 0.42). In conclusion, neither breastfeeding nor the timing of the introduction of complementary foods was associated with adiposity at 5 years.

Daniels et al. [13, 14] came up with the NOURISH randomized control study whose objective was to evaluate outcomes of a universal intervention initiated in infancy with the purpose to prevent childhood obesity. 698 first-time mothers were enrolled (mean age ± SD: 30.1 ± 5.3 years) with healthy term infants (51% female) aged 4.3 ±

1.0 months at baseline. Mothers were randomly allocated to usual care which included self-directed access to modules or to attend two 6-session interactive group education modules that provided anticipatory guidance on early feeding practices. Outcomes were assessed 6 months after completion of the second information module, 20 months from baseline, and when the children were 2 years old. The results demonstrated that the mothers in the intervention group reported using responsive feeding more frequently on 6 of 9 subscales and 8 of 8 items (all, p ≤ 0.03)and overall less controlling feeding practices (p < 0.001). In conclusion, evaluation of NOURISH data of children aged 2 years found that anticipatory guidance on complementary feeding, tailored to developmental stage, increased first-time mothers' use of "protective" feeding practices that potentially support the development of healthy eating and growth patterns in young children. Wider promotion of current infant feeding guidelines could have a significant impact on the rates of childhood obesity.

Conclusion

The relationship between complementary feeding and childhood obesity has been suspected for a long time, through specific risk parameters are not as firmly established. In this review, early introduction of complementary feeds (before the 4th month of life), high protein and energy content of the feeds, and nonadherence to evidence-proven feeding guidelines may be associated with overweight and obesity later in life.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to dis. Wider promotion of current infant feeding guide-close. The writing of this article was supported by Nestlé Nutrition.

References

- Ahmad QI, Ahmad CB, Ahmad SM: Childhood Obesity. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2010;14:19–25.

- WHO fact sheet on childhood obesity. http:// www.who.int/end-childhood-obesity/facts/ en/. October 2017 (last accessed in January 2018).

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM: Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the united states, 2011–2012. JAMA 2014; 311:806–814.

- Stettler N, Zemel BS, Kumanyika S, Stallings VA: Infant weight gain and childhood overweight status in a multicenter, cohort study. Pediatrics 2002;109:194–199.

- Wang G, Johnson S, Gong Y, Polk S, Divall S, Radovick S, et al: Weight gain in infancy and overweight or obesity in childhood across the gestational spectrum: a prospective birth cohort study. Sci Rep 2016;6:29867.

- Magarey AM, Daniels LA, Boulton TJ, Cock-ington RA: Predicting obesity in early adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003;27:505.

- Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Sherry B, et al: Crossing growth percentiles in infancy and risk of obesity in childhood. Arch Pediatr Ad-olesc Med 2011;165:993–998.

- Pearce J, Taylor MA, Langley-Evans SC: Timing of the introduction of complementary feeding and risk of childhood obesity: a systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37: 1295.

- Wang J, Wu Y, Xiong G, Chao T, Jin Q, Liu R, et al: Introduction of complementary feeding before 4 months of age increases the risk of childhood overweight or obesity: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Nutr Res 2016;36:759–770.

- Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Belfort MB, Kleinman KP, Oken E, Gillman MW: Weight status in the first 6 months of life and obesity at 3 years of age. Pediatrics 2009;123:1177– 1183.

- Seach KA, Dharmage SC, Lowe AJ, Dixon JB: Delayed introduction of solid feeding reduces child overweight and obesity at 10 years. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010;34:1475.

- Burdette HL, Whitaker RC, Hall WC, Daniels SR: Breastfeeding, introduction of complementary foods, and adiposity at 5 y of age. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:550–558.

- Daniels LA, Mallan KM, Nicholson JM, Bat-tistutta D, Magarey A: outcomes of an early feeding practices intervention to prevent childhood obesity. Pediatrics 2013;132:e109e118.

- Daniels SR, Hassink SG: The role of the pediatrician in primary prevention of obesity. Pediatrics 2015;136:e275–e292.

Reprinted with permission from: Laving/Hussain/AtienoAnn Nutr Metab 2018;73(suppl 1):15–18 DOI: 10.1159/000490088