Complementary Feeding - Beyond Nutrition

Focus

Key insights

During the weaning period infants experience important biological and neurodevelopmental milestones. The transition from breastfeeding to solid foods requires gastrointestinal maturity as well as the physical capacity to hold the head and trunk upright. Current research indicates that 4–6 months of age is a suitable period for the introduction of complementary foods. As children transition to the family diet, recommendations should address not only the type of foods but also the social context of eating.

Current knowledge

Eating not only impacts the infant’s physical growth but also the emotional and psychosocial development. Exposure to a variety of food items, including fruits and vegetables, is associated with acceptance of these foods in later life. The behavior of the caregiver and the child’s temperament affect the feeding relationship. Strategies such as punishment and distraction tend to aggravate potential feeding problems in the long term. The most effective approach is responsive feeding, whereby the caregiver responds to the child’s cues of hunger and satiety and allows the child to set the pace for the timing and amount of a meal.

Practical implications

The success of complementary feeding requires the convergence of several factors. Adequate dietary diversity and appropriate food amounts must be coordinated with the correct timing. To this end, the cultural beliefs, educational level, and

wealth status of the caregivers are key contributing factors. Education, both at the household and community level, is moving to the forefront as one of the most important modifiable influences on complementary feeding. Appropriate parental education is necessary to overcome the common difficulties faced (such as early food refusal) and to facilitate the successful transition to a varied, nutrient-rich diet.

Recommended reading

Mennella JA, Nicklaus S, Jagolino AL, et al: Variety is the spice of life: strategies for promoting fruit and vegetable acceptance during infancy. Physiol Behav 2008;94:29–38.

Key Messages

- The introduction of complementary feedings requires gastrointestinal and neuromuscular development for it to be successful.

- Research has led to recommendations regarding the timing of introduction between 4 and 6 months of age.

- Problems in the suck-swallow function and/or psychosocial issues can lead to a problematic initiation of complementary feedings.

Keywords

Swallowing · Dysphagia · Intestinal maturity · Feeding disorders

Abstract

In this article, we will summarize the key non-nutritional aspects of the introduction of complementary feeding. Intestinal maturation related to starch digestion is relatively complete by the time complementary feeding is recommended to be initiated. A much more complex maturation is needed, however, from the neurodevelopmental standpoint as the infants need to be able to hold their head and trunk and be able to coordinate tongue movement followed by swallowing. Issues can arise in infants with a history of medical problems as well as when caretakers cannot handle the initial difficulties or want to impose certain rigidity to the learning process. The introduction of complementary feedings is also part of the early steps in introduction to human socialization. In that regard, it sets up the infant to internalize and accept the diversity of food textures and food choices. Early refusal of some food items is common and should not be interpreted as being disliked. Multiple attempts should be made to incorporate new food items. To accomplish these dynamics, caregivers need comprehensive education and relevant information.

Introduction

The incorporation of complementary feeding is the first major proactive step in the infant’s life towards “growing up.” It requires a series of neurodevelopmental achievements and it becomes a way of socialization. In this article, we will summarize the digestive and non-nutritional aspects of the introduction of complementary feeding.

Physiological Aspects

From the Digestive Standpoint

The weaning period is defined as the one that begins with the introduction of a nonmilk diet and ends with the cessation of intake of breastmilk (or formula). In rats, for example, there are precise and sudden changes in the intestinal capacity to digest nonmilk carbohydrates such as an increase in proliferation of enterocytes as well as the mucosal expression of such enzymes as sucrase-isomaltase activities [1–3] .

Several of the weaning foods are cereal-based, where starch becomes a new nutrient to the digestive system which until then had only been exposed to milk. Compared to studies and subsequent recommendations on the benefits of breastfeeding in providing optimal nutrition and immune maturation among others [4–6] , until not that long ago, the importance of weaning had received less interest [7] .

Because of obvious reasons, the physiology of the digestive system is less well understood in the human infant than in the animal model, mainly the timing of the mechanisms involved in adaptation to a nonmilk diet. As it is to be expected, the physiology of the young infant’s gastrointestinal tract is not the same as that of the adult; for starters, most digestive enzymes are found at much lower concentrations. The concentration of pancreatic a-amylase in the neonatal duodenum is much lower than in adults [8, 9] . Serum concentrations of pancreatic a-amylase at birth are 1.6% of the adult levels and do not reach mature levels until 5–12 years [10].

Pancreatic fluid and electrolyte secretion increase in response to secretin and cholecystokinin [11] ; however, assays specific for a-amylase indicate that infants younger than 1 month do not respond to cholecystokinin and only have a minimal response to secretin [12]. However, plasma concentration of gastrointestinal hormones, including secretin, remain low until the sixth day of life [13]. Whether in early infancy synthesis or secretion of a-amylase is low and/or there is low production of, or response to, secretagogues, is not clear.

Starch digestion begins in the mouth as a result of the action of the enzyme a-amylase, a glycoprotein secreted in saliva and human milk and responsible for the cleavage of the linear a-1,4 linkages (linear ones) in the starch molecule. Although a-amylase becomes inactive in the stomach as a consequence of gastric acid, the process of digestion continues when the bolus arrives to the duodenum which has an alkaline pH. Once there, there is reactivation of the salivary isozyme, to which the action of another a-amylase secreted by the exocrine pancreas is added. As a result of this digestive process, maltose, isomaltose, maltotriose, as well as the branched-chain oligosaccha-rides maltodextrins will be generated and undergo additional digestion at the level of the brush border of the jejunal mucosa. Finally, free glucose is liberated by the action of glucoamylase, maltase, and isomaltase which is then transported across the mucosa by an active mechanism [14] . From in vitro studies it is known that there is a wide range in the degree of digestibility of commonly used first weaning foods [15].

For example, rice starch is rapidly digestible as well as freshly boiled potato; however, the latter may become retrograded and resistant if cooled after cooking. On the other hand, sterilizing techniques in the canning of commercial weaning foods may considerably increase the resistant starch content of the diet of the young child [16] and the consequent effects on energy absorption and growth potential are unknown [17, 18] .

Studies on pancreatic amylase activity were originally only carried out in vitro. In 1975, an Italian study [18] added starch from different sources (potato, tapioca, corn, wheat, and rice) to 1- to 3-month-old babies’ formulas and determined fecal output. Results indicated that very little starch was excreted in stools. When the infants received between 1 tablespoon and 1/2 of a cup of starch per day, they appeared to digest more than 99% of it. The investigators then tried a larger dose, giving several 1-month-olds a full cup of rice starch. Three of these infants absorbed more than 99% of this amount, two absorbed 96%, while 4% of the starch was excreted in stools, some of whom had diarrhea. In other words, within the first few months of life, babies can digest small amounts of starch just fine, but give them too much and you will see some diarrhea.

Shulman et al. [19] performed a study in which direct demonstration of cereal utilization by 16 healthy 1-month-old infants was achieved by tracing the appearance in breath CO2 of carbon derived from the fed cereal. Fermentation of unabsorbed carbohydrate by the colonic flora was assessed by measurement of breath hydrogen. Stools from 4 infants were analyzed for the quantity of carbon that originated from the cereal. The authors concluded that young infants can utilize cereal, although absorption is not always complete. Hydrogen production increases with carbohydrate complexity; participation of colonic bacterial fermentation increases the net absorption of cereal.

In view of the current recommendations of not initiating complementary feedings prior to 4 months of age, it is likely that the infant’s intestinal digestion capacity can handle reasonable amounts of cereal fed by that time. Whatever is not digested or absorbed, colonic microbiota will ferment and utilize.

Physiology of Deglutition

The act of drinking and eating can be divided into 4 main components: (1) the oral phase (i.e., suckling or mastication followed by transportation of the bolus to the pharynx), (2) the triggering of the swallow reflex, (3) the pharyngeal phase (transport of the bolus through the pharynx), and (4) the esophageal phase (i.e., transport of the bolus into the stomach through the esophagus).

In the newborn as well as in young infants, all 4 components described above are reflexive and involuntary. Only later in infancy, the oral phase becomes controlled voluntarily which is an essential achievement in order to allow infants to begin to masticate solid food. For mastication to be safe and effective (i.e., biting and chewing) there has to be an appropriate sensory registration of the food source as well as a coordinated motor response connected to cognitive thought processes. In later life, triggering of the swallow reflex becomes a mostly involuntary activity, although voluntary control is also possible. However, the pharyngeal and esophageal phases of swallowing are involuntary activities. Regardless of these maturational changes, the general sequence of events of swallowing during the pharyngeal and esophageal phases remain unchanged throughout life.

Feeding Problems

Feeding problems are roughly divided into organic, behavioral, or a combination of both [20, 21] . Organic feeding disturbances may be the consequence of cranio-facial malformations, lung and cardiac illnesses, neurological dysfunction, etc. [20] .

Although behavioral feeding disturbances may arise associated with dysphagia, in general there is no obvious organic reason for behavioral feeding problems. Tonsillitis, pharyngitis, or even teething, negative experiences in or around the mouth, such as tube feeding, prolonged need for suctioning of secretions, or sensory disturbances (oral hypersensitivity) need to be considered before attributing a feeding difficulty just to behavior.

Some of the feeding problems are food refusal, disruptive behavior at mealtime, rigid food acceptance, and failure to master self-feeding skills according to the child’s developmental abilities. Generally, younger children have more feeding problems than do older ones. The fact is that if they go untreated, feeding problems continue to persist. Some research also shows that feeding problems may evolve into eating disorders in adolescence and adulthood [22].

When feeding skills are intact and appetite is appropriate, feeding times, and as the child grows older, mealtime is an occasion of pleasant socialization with a result of adequate nutrient intake leading to adequate growth. Willingness to eat at appropriate times and intervals, drinking and eating in good rhythm, trying new food textures and flavors, and expressing satisfaction at the end of feeding are considered appropriate feeding behaviors which lead to positive feeding interactions and consequently reinforce the feeling of self-mastery in the young child, resulting in continued food acceptance and progressively reaching independent feeding behaviors. On the other hand, whenever feeding skills are impaired, be it by poor oro-motor skills, extreme sensitivity to texture and/or taste and/or poor appetite, this results in problematic feeding behaviors such as not feeling hunger, sucking or eating extremely slowly, gagging or refusing to take food to the mouth. Particularly in young infants, associative conditioning to painful gastrointestinal cues often manifests itself in problematic feeding behaviors.

Temperamental Characteristics and Regulatory Capacities

Poor weight gain or the caretaker’s perception of inadequate food intake may result in maternal attempts to increase the infant’s nutrient intake by either feeding more frequently, forcing food into their mouth, or both, which may result in stressful and unpleasant feeding experiences for both. Although not always, these efforts may initially achieve their purpose of maintaining some weight gain, but sooner or later they become ineffective and maladjusted mother-infant/child interactions and behavioral mismanagement may develop. However, addressed early, most eating problems are temporary and easily resolved with little or no special intervention. However, problems that persist can impinge on the children’s growth, development, and relationships with their caregivers. Feeding is a primary event in the life of an infant and it is the focus of attention for parents and other caregivers.

Behavioral and Social Aspects of Feeding/Eating

The act of eating not only results in the intake of nutrients but also provides an opportunity for learning. Eating not only has an impact on the infant’s physical growth and overall health but also on their emotional and psychosocial development. The first stage of development takes runs from birth to 3 months when the infant learns self-regulation and organization [23].

The infant starts to integrate experiences of hunger and satiety and to develop a regular feeding pattern. In the second stage, that runs from 3 to 7 months of age, the infant and parent develop an attachment allowing them to interchange communication, while the infant develops behaviors such as basic trust and self-soothing. Finally, in the third stage, from 7 to 36 months of age, the child gradually emotionally “separates” from the parent and discovers a sense of autonomy and independence.

Rapid developmental changes related to eating characterize the first year of life. Once infants gain truncal control, they are able to progress from just sucking liquids in a supine or semi-reclined position to eating semisolid and then solid foods in a seated position. In parallel, oral motor skills advance from a basic suck-swallow mechanism with breast milk or formula to a more complex chew-swallow with semisolids, progressing to complex textures. In addition, as infants gain fine motor control, they are able to advance from being completely fed by others to at least a partial self-feeding. The diet expands from breastmilk or formula to purees and then chopped food, to eventually the family diet. By the end of the first year of life, children can sit independently, chew and swallow a range of textures, feed themselves partially, and are making the transition to the family diet and meal patterns.

As children transition to the family diet, recommendations address not only food, but also the eating context. A variety of healthy foods promote diet quality, along with early and sustained food acceptance. Data gathered on infants and young children 6–23 months of age across countries demonstrated a positive association between dietary variety and nutritional status [24] . Exposure to fruits and vegetables in infancy and toddlerhood have been associated with acceptance of these foods at later ages [25–27] .

Both the caregiver’s behaviors as well as the child’s temperament influence the feeding relationship [23] . A parent who allows the infant to determine timing, amount, and pacing of a meal helps the infant develop self-regulation and secure attachment. When the child’s signals are misinterpreted, it can lead to or aggravate further problematic feeding behaviors. As said before, strategies to encourage eating such as punishment (in older children), distraction, and toys can work temporarily, but then tend to worsen the problems over time. The most effective approach is responsive feeding, when reciprocal interactions during meals are based on the child’s signals and are age appropriate.

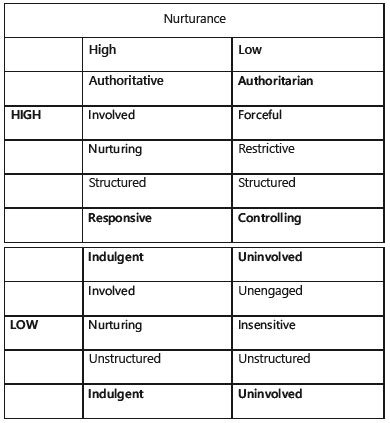

Fig. 1. The caregiver-child feeding context: patterns of parenting and feeding. With permission from [23] .

Farrow and Blissett [28] carried out a study in which 87 women completed questionnaires regarding breastfeeding, assessing their control over child-feeding and mealtime negativity at 1 year of infant age. Seventy-four of these women were also observed feeding their infants solid food at 1 year. Mediation analyses demonstrated that the experience of breastfeeding, mediated by lower reported maternal control over child-feeding, predicted maternal reports of less negative mealtime interactions. The experience of breastfeeding also predicted observations of less conflict at mealtimes, mediated by observations of maternal sensitivity during feeding interactions. Variability in the caregiver-child feeding context is related to children’s eating behavior and growth [23, 29].

The dimensions of parental structure and nurturance, which incorporate parents’ perceptions of their child’s behavior, have been applied to the feeding context ( Fig. 1 ) [23, 30–32] .

The Importance of Caregiver Knowledge

Appropriate complementary feeding involves ensuring qualitative (commencing at the correct time, adequate dietary diversity) and quantitative (frequency and amount against age) aspects [33] . An additional index combining appropriate frequency and diversity known as minimum acceptable diet is also often reported by the caregiver, and overall societal knowledge and cultural believes are known to be key drivers of all these aspects of complementary feeding along with food availability, largely determined by household wealth.

A systematic review of complementary feeding practices in South Asian Infants identified low education and ill-understood policies in infant and young child feeding (at community level) among the top barriers to appropriate complementary feeding practices [34] . A publication of data from 5 individual South Asian countries also reported a lack of maternal education and lower household wealth as the most consistent determinants of inappropriate practices in complementary feeding [35] . Three related studies from across Sub-Saharan Africa all reported a similar association between maternal/community education and appropriate complementary feeding [36–38] . The Ethiopian study using mothers’ interviews found rates of 72.5, 67.3, and 18.8% of appropriate knowledge/practice regarding timing of initiation, minimum meal frequency, and minimum dietary diversity, respectively [36] .

From these findings, the importance of education at the household and community level cannot be overemphasized as an indirect contributor towards appropriate complementary feeding among the most important.

Conclusions

The successful introduction of complementary feeding requires a mature digestive system and the acquisition of some essential neurodevelopmental milestones. Progressive exposure of the infant to a variety of textures and tastes, administered in the appropriate condition including timing and amounts, should lead to a successful transition to the second year of life and incorporation of family foods. Appropriate parental education is needed to avoid common mistakes which are usually transient but that sometimes can lead to lengthier situations that are more difficult to resolve.

Disclosure Statement

F.N.W. and C.L. are members of the Faculty Board of the Nestlé Nutrition Institute. C.L. has received honoraria from Da-none, Mead Johnson Nutrition, and IPSEN Pharma. F.N.W. is also a board member of the Nestlé Nutrition Institute Africa and has received an honorarium from MERCK. The writing of this article was supported by Nestlé Nutrition Institute.

References

- Henning SJ: Postnatal development: coordination of feeding, digestion, and metabolism. Am J Physiol 1981;241:G199–G214.

- Buddington RK: Nutrition and ontogenetic development of the intestine. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 1994;72:251–259.

- Lin AH, Hamaker BR, Nichols BL Jr: Direct starch digestion by sucrase-isomaltase and maltase-glucoamylase. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012; 55(suppl 2):S43–S45.

- American Academy of Pediatrics: Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 2012;129:e827–e841.

- World Health Organization: The World Health Organization’s Infant Feeding Recommendation. http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/infantfeeding_recommendation/ en/index.html (accessed March 23, 2018).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: U.S. Breastfeeding Rates Are Up! More Work Is Needed. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/breast-feeding/resources/us-breastfeeding-rates. html (accessed March 23, 2018).

- Wharton BA: Food for the weanling: the next priority in infant nutrition. Acta Pediatr Scand 1986;323:96–102.

- Zoppi G, Andreotti F, Pajno-Ferrara F, et al: Exocrine pancreas function in premature and full term neonates. Pediatr Res 1972;6:880– 886.

- Lebenthal E, Lee PC: Development of functional response in human exocrine pancreas. Pediatrics 1980;66:556–560.

- Gillard BK, Simbala JA, Goodglick L: Reference intervals for amylase isoenzymes in serum and plasma of infants and children. Clin Chem 1983;29:1119–1123.

- Zoppi G, Andreotti G, Pajno-Ferrara F, et al: The development of specific responses of the exocrine pancreas to pancreozymin and se-cretin stimulation in newborn infants. Pediatr Res 1973;7:198–203.

- Poquet L, Wooster TJ: Infant digestion physiology and the relevance of in vitro biochemical models to test infant formula lipid digestion. Molec Nutr Food Res 2016;60:1876– 1895.

- Lucas A, Adrian TE, Christofides M, et al: Plasma motilin, gastrin enteroglucagon and feeding in the human newborn. Arch Dis Child 1980;55:673–677.

- Waasdorp Hurtado C: Carbohydrate Digestion and Absorption. NASPGHAN Physiology Series. https://www.naspghan.org//files/ documents/pdfs/training/curriculum-resources/physiology-series/Carbohydrate_di-gestion_NASPGHAN.pdf.

- Gahlawat P, Sehgal S: In vitro starch and protein digestibility and iron availability in weaning foods as affected by processing methods. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 1994;45:165–173.

- Bjorck IME, Siljestrom MA: In vivo and in vitro digestibility of starch in autoclaved pea and potato products. J Sci Food Agric 1992; 58:541–553.

- Crawford P: Resistant starch and infant nutrition. J Nutr Educ1993;25:319.

- De Vizia B, Ciccimarra F, De Cicco N, et al: Digestibility of starches in infants and children. J Pediatr 1975;86:50–55.

- Shulman RJ, Wong WW, Irving CS, et al: Utilization of dietary cereal by young infants. J Peds 1983;103:23–28.

- Rybak A: Organic and nonorganic feeding disorders. Ann Nutr Metab 2015; 66(suppl 5): 16–22.

- Kerzner B, Milano K, Mac Lean W Jr, et al: A practical approach to classifying and managing feeding difficulties. Pediatrics 2015;135: 344–353.

- Marchi M, Cohen P: Early childhood eating behaviors and adolescent eating disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1990;29: 112–117.

- Black MM, Hurley KM: Helping children develop healthy eating habits; in Tremblay RE, Boivin M, Peters RD (eds): Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development. Centre of Excellence for Early Childhood Development (CEECD) and the Strategic Knowledge Cluster on Early Child Development (SKC-ECD), 2013–2017. Online access at: http://www. child-encyclopedia.com/child-nutrition/ac-cording-experts/helping-children-develophealthy-eating-habits.

- Arimond M, Ruel MT: Dietary diversity is associated with child nutritional status: Evidence from 11 demographic and health surveys. J Nutr 2004;134:2579–2585.

- Skinner JD, Carruth BR, Bounds W, et al: Do food-related experiences in the first 2 years of life predict dietary variety in school-aged children? J Nutr Educ Behav 2002;34:310–315.

- Schwartz C, Scholtens PA, Lalanne A, et al: Development of healthy eating habits early in life. Review of recent evidence and selected guidelines. Appetite 2011;57:796–807.

- Mennella JA, Nicklaus S, Jagolino AL, et al: Variety is the spice of life: strategies for promoting fruit and vegetable acceptance during infancy. Physiol Behav 2008;22;94:29–38.

- Farrow C, Blissett J: Breast-feeding, maternal feeding practices and mealtime negativity at one year. Appetite 2006;46:49–56.

- Rhee K: Childhood overweight and the relationship between parent behaviors, parenting style, and family functioning. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 2008;615:11–37.

- Baumrind D: Rearing competent children; in Damon W (ed): Child Development Today and Tomorrow. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1989, pp 349–378.

- Maccoby EE, Martin J: Socialization in the context of the family: parent-child interaction; in Hetherington EM (ed): Handbook of Child Psychology: Socialization, Personality, and Social Development. New York, John Wiley, 1983, vol 4, pp 1–101.

- Black MM, Aboud FE: Responsive feeding is embedded in a theoretical framework of responsive parenting. J Nutr 2011;141:490–494.

- WHO: Complementary feeding. http://www. who.int/nutrition/topics/complementary_ feeding/en/.

- Manikam L, Robinson A, Kua JY, et al: A systematic review of complementary feeding practices in South Asian infants and young children: the Bangladesh perspective. BMC Nutrition 2017;3:56.

- Seranath U, Agho KE, Samin D, et al: Comparison of complementary feeding indicators and associated factors in children aged 6–23 months across five South Asian Countries. Matern Child Nutr 2012; 8(suppl 1): 89–106.

- Kassa T, Meshesha B, Haji Y et al: Appropriate complementary feeding practices and associated factors among mothers of children age 6–23 months in Southern Ethiopia, 2015. BMC Pediatr 2016;16:131.

- Frempong RB, Annin SK: Dietary diversity and child malnutrition in Ghana. Heliyon 2017;3:e00298.

- Mitchodigni IM, Hounkpatin WA, Ntandou-Bouzitou G: Complementary feeding practices: determinants of dietary diversity and meal frequency among children aged 6–23 months in Southern Benin. Food Sec 2017;9:1117.

Complementary Feeding: Beyond Reprinted with permission from: Nutrition Ann Nutr Metab 2018;73(suppl 1):20–25 DOI: 10.1159/000490084